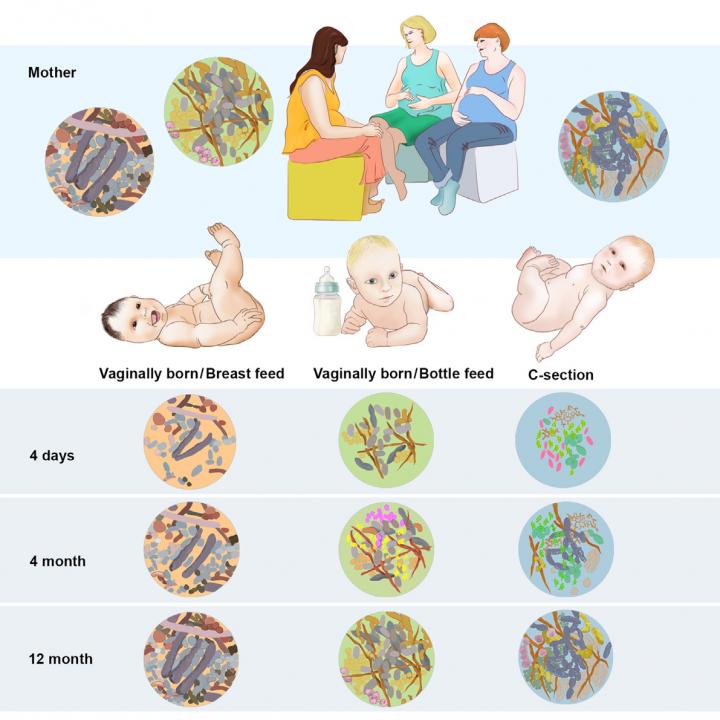

It’s widely accepted that the delivery mode, whether vaginally or C-section, shapes the manner in which an infant’s healthy microbiota are established. Vaginal deliveries are preferred to help colonize an infant’s healthy bacteria. A new study, published in Cell Host & Microbe, confirmed this understanding and found the cessation of breastfeeding is a significant catalyst for the development of adult-like microbiota.1

“Our findings surprisingly demonstrated that cessation of breastfeeding, rather than introduction of solid foods, is the major driver in the development of an adult-like microbiota,” says lead study author Fredrik Bäckhed of The University of Gothenburg, Sweden. “However, the effect of an altered microbiome early in life on health and disease in adolescence and adulthood remains to be demonstrated.”

Recent science shows that gut bacteria are themselves a source of nutrients and vitamins. Their adaptive nature and interaction with other cellular processes plays a significant role in the infant’s metabolism, immunity and even cognitive health.3

This new study supports previous observations that most early bacterial colonizers of the gut are derived from the mother.4,5 The investigators noted that while C-section babies receive less of their mother’s microbes, they are still passed on through the skin and mouth.

“Our results underscore the role of breast-feeding in the shaping and succession of gut microbial communities during the first year of life,” the authors write. “The gut microbiota of children no longer breast-fed was enriched in species belonging to Clostridia that are prevalent in adults, such as Roseburia, Clostrium, and Anaerostipes. In contrast, Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus still dominated the gut microbiota of breast-fed infants at 12 months.”

For more research in how an infant’s gut microbiata develops up to age three, click here to read: Breastfeeding and Intestinal Microbiota.

1. F Bäckhed et al. Dynamics and Stabilization of the Human Gut Microbiome during the First Year of Life. Cell Host Microbe. 2015 May 13;17(5):690-703.

2. The infant gut microbiome: New studies on its origins and how it’s knocked out of balance. Press Statement, Eureka Alert, May 13, 2015.

3. M Aguirre et al. The art of targeting gut microbiota for tackling human obesity. Genes Nutr. 2015 Jul;10(4):472.

4. G Biasucci G et al. Cesarean delivery may affect the early biodiversity of intestinal bacteria. J Nutr. 2008 Sep;138(9):1796S-1800S.

5. MM Grönlund MM, et al. Fecal microflora in healthy infants born by different methods of delivery: Permanent changes in intestinal flora after Cesarean delivery.J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.1999;28:19–25.

6. M Gueimonde M et al. Breast milk: a source of bifidobacteria for infant gut development and maturation? Neonatology. 2007;92(1):64-6.

7. ibid, Eureka Alert.

8. P Vangay P, et al. Antibiotics, Pediatric Dysbiosis, and Disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2015 May 13;17(5):553-564. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.04.006.

9. Fujimura KE, Lynch SV. Microbiota in Allergy and Asthma and the Emerging Relationship with the Gut Microbiome. Cell Host Microbe. 2015 May 13;17(5):592-602.

This article written and edited from materials presented by Cell Host & Microbe