With the massive interest in the use of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists for the management of both Type 2 diabetes and obesity/overweight, it is timely to review the mode of action of these medications and that of an alternative GLP-1-stimulating nutraceutical.

Production of GLP-1

After a meal, endogenous GLP-1 is produced in a biphasic manner, with an initial rapid rise 15-30 minutes after eating, and a second minor peak 1-2 hours later.1 GLP-1 is primarily released from enteroendocrine ‘L cells’ in the intestinal epithelium that have microvilli which sense the contents of the gut.2 When stimulated by nutrients, they release GLP-1 granules at their basal side (away from the gut lumen). The primary pathway of GLP-1 activity is thought to be via neuropods (i.e., synapses between the enteroendocrine cells and afferent branches of the vagus nerve) which transmit signals to certain nuclei in the brainstem. Those nuclei themselves produce GLP-13 and also send axons to the hypothalamus.4

In addition, some GLP-1 is taken up by capillaries and delivered to the hepatoportal vein and circulation, but the majority is rapidly inactivated by dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4), leaving <10% of intestinal GLP-1 available to peripheral organs.4

GLP-1 Receptors

GLP-1 receptors are present in multiple sites throughout the body. They are most concentrated in beta cells of the pancreas, so it’s suggested that even the small amount of active GLP-1 that reaches it via the circulation may activate receptors there to increase insulin secretion.2 In the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, GLP-1 receptors are found at various levels of expression in the stomach, small intestine and proximal colon, and in the myenteric plexus.

GLP-1 receptors are also distributed throughout the brain, and at a high level in the brainstem and hypothalamus. Activation of brain GLP-1 receptors generates signals to target organs via the autonomic nervous system and also has local neurotransmitter effects within the brain itself.5

Effects of GLP-1 Receptor Activation

Despite the discovery of vagal neuropods, there is some debate whether there is a direct link between activation of GLP-1 receptors in the gut and those in the brain.5 Whatever the method of brain GLP-1 receptor activation, the local brain effects are to increase satiety.

Within the GI system, GLP-1 delays gastric emptying, increases insulin production, increases glucose uptake in the liver, and more. GLP-1 may also affect muscle utilization of glucose and lipid storage in white adipose tissue.2,4 In the heart, it increases heart rate and blood pressure, and decreases vasodilation.4

Amarasate® Mode of Action

Amarasate® is an extract of bitter hops flowers cultivated in New Zealand and encapsulated in the USA. Unlike drugs such as semaglutide or tirzepatide, Amarasate is not an exogenous form of GLP-1, but rather, stimulates the body’s own production of this and other GI hormones. Its mode of action is via bitter taste receptors (TAS2Rs), which are present throughout the GI tract (from the tongue to the colon). TAS2Rs are thought to evolutionarily protect against potentially harmful substances. In the GI tract, they are present on enteroendocrine cells that produce a range of gut hormones (including GLP-1, cholecystokinase [CCK], and peptide YY [PYY]) when the TAS2R is activated by a bitter substance. Amarasate® capsules are formulated to release in the duodenum, as early research determined that site had the highest high level of TAS2Rs on enteroendocrine cells in the gut.

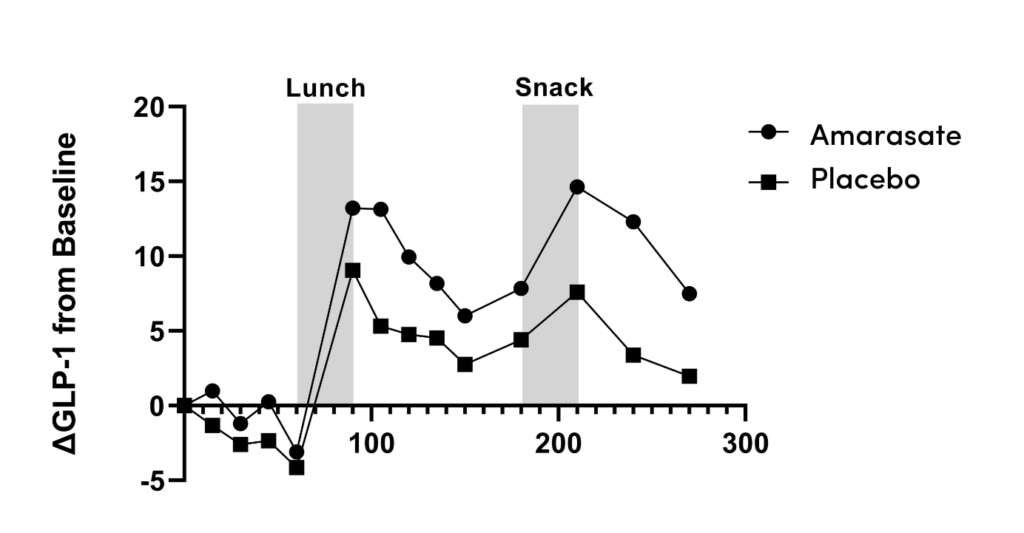

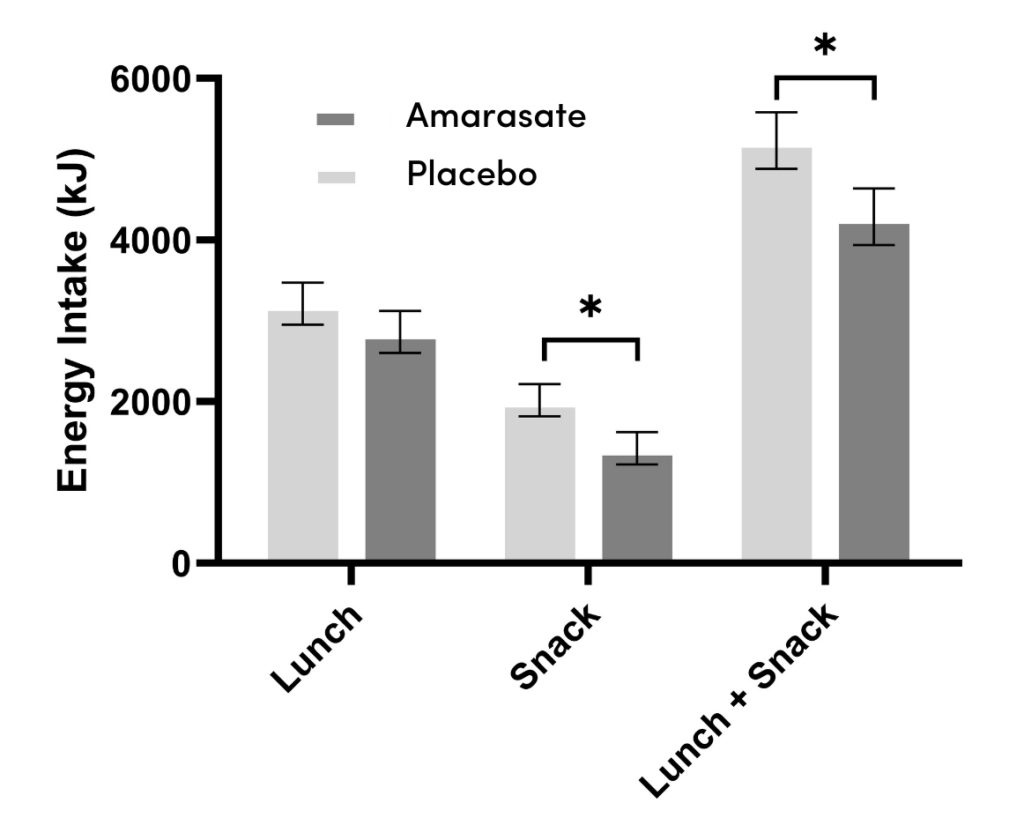

In a study of healthy men, Amarasate®’s mode of action was confirmed as being a potent stimulant of endogenous production of gut hormones, including GLP-1, CCK, and PYY.6 Taken an hour before a meal, this nutraceutical increased basal levels of GLP-1 and CCK to six times above baseline, and to twice the typical release occurring after eating (Figure 1).6 Moreover, Amarasate® enhanced the release of GLP-1 and other hormones in the same physiological pattern seen normally. This resulted in a reduction of caloric intake at subsequent meals of 18% (Figure 2).6 Two further clinical trials demonstrated that Amarasate® reduced hunger in fasting men,7 and hunger and food cravings in fasting women.8 A subsequent trial is currently enrolling adults with a BMI of at least 30, with a primary endpoint of weight loss following 6 months of therapy.

With the duodenal release of Amarasate®, nausea is rarely reported with its use. Diarrhea may occur in up to 10% of individuals when starting the product, so it is advised to gradually introduce it.

Amarasate® is taken an hour before a meal, initially as 1 capsule daily and gradually building up to 2 capsules before two meals a day, if needed. There are differences in individual responses to Amarasate®; whether this is due to increased sensitivity of TAS2Rs to bitter compounds (producing even greater GLP-1 enhancement) or to increased sensitivity to GLP-1 effects is unclear. Consequently, some users may require only 1 or 2 capsules a day, whereas others may need a higher dose to experience an increase in satiety adequate enough to reduce food intake sufficiently that they lose weight.

GLP-1 Receptor Agonists

GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) are based on analogs of the human molecule that are resistant to DPP-4, or a molecule derived from the saliva of the Gila monster lizard (!).9 Most are administered as subcutaneous injections, although semaglutide now has an oral form. The two agents indicated for weight loss are semaglutide (a GLP-1 analog) and tirzepatide (an analog of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide [GIP] that activates both GIP and GLP-1 receptors). Both are administered once weekly (or once daily for oral semaglutide). The effects on weight loss have been well documented. In the STEP 1 and STEP 3 trials, mean weight loss after 68 weeks of semaglutide was around 15%.10 The SURMOUNT-1 trial demonstrated weight loss of 15-21% after 72 weeks of tirzepatide (5, 10 or 15 mg).11

Adverse events with these agents are not uncommon and are typically GI in nature: dyspepsia, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. With semaglutide (whether subcutaneous or oral), nausea increases in proportion to circulating levels of this GLP-1 RA12. Other side effects include dizziness, mild tachycardia, infections, and headache. There is a discontinuation rate of around 10%.13

The very high, sustained, and non-physiological levels of exogenous GLP-1 resulting from the administration of these agents may likely explain both some of the mode of action and the adverse effects of GLP-1 RAs. In addition to their systemic effects at GLP-1 receptors throughout the body, the high circulating levels achieved may be sufficient to directly activate receptors in the brain.5 This may explain the gastrointestinal side effects of GLP-1 RAs, for example, continuing nausea even when delayed gastric emptying is no longer occurring due to tachyphylaxis, and gastroparesis in the absence of nausea — both of which are probably due to the high level of CNS receptor activation produced by them.2

Figures

Figure 1: Changes in post-prandial plasma levels of GLP-1 after placebo or Amarasate®.6

Figure 2: Change in energy intake after Amarasate® or placebo taken an hour before lunch.6

References

- Shah M, Vella A. Effects of GLP-1 on appetite and weight. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. Sep 2014;15(3):181-7. doi:10.1007/s11154-014-9289-5

- Holst JJ, Andersen DB, Grunddal KV. Actions of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor ligands in the gut. Br J Pharmacol. Feb 2022;179(4):727-742. doi:10.1111/bph.15611

- Holt MK, Richards JE, Cook DR, et al. Preproglucagon Neurons in the Nucleus of the Solitary Tract Are the Main Source of Brain GLP-1, Mediate Stress-Induced Hypophagia, and Limit Unusually Large Intakes of Food. Diabetes. Jan 2019;68(1):21-33. doi:10.2337/db18-0729

- Cabou C, Burcelin R. GLP-1, the gut-brain, and brain-periphery axes. Rev Diabet Stud. 2011;8(3):418-31. doi:10.1900/RDS.2011.8.418

- Trapp S, Brierley DI. Brain GLP-1 and the regulation of food intake: GLP-1 action in the brain and its implications for GLP-1 receptor agonists in obesity treatment. Br J Pharmacol. Feb 2022;179(4):557-570. doi:10.1111/bph.15638

- Walker EG, Lo KR, Pahl MC, et al. An extract of hops (Humulus lupulus) modulates gut peptide hormone secretion and reduces energy intake in healthy-weight men: a randomized, crossover clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr. Mar 04 2022;115(3):925-940. doi:10.1093/ajcn/nqab418

- Walker EG, Lo KR, Tham S, et al. New Zealand Bitter Hops Extract Reduces Hunger During a 24 h Water Only Fast. Nutrients. 2019;11(11):2754. Published 2019 Nov 13. doi:10.3390/nu11112754

- Walker EG, Lo KR, Gopal P. Gastrointestinal delivery of bitter hops extract reduces appetite and food cravings in healthy adult women undergoing acute fasting. Preprints 2023, 2023090416. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202309.0416.v1

- Yu JH, Park SY, Lee DY, Kim NH, Seo JA. GLP-1 receptor agonists in diabetic kidney disease: current evidence and future directions. Kidney Res Clin Pract. Mar 2022;41(2):136-149. doi:10.23876/j.krcp.22.001

- Elmaleh-Sachs A, Schwartz JL, Bramante CT, Nicklas JM, Gudzune KA, Jay M. Obesity Management in Adults: A Review. JAMA. Nov 28 2023;330(20):2000-2015. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.19897

- Jastreboff AM, Aronne LJ, Stefanski A. Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity. Reply. N Engl J Med. Oct 13 2022;387(15):1434-1435. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2211120

- Overgaard RV, Hertz CL, Ingwersen SH, Navarria A, Drucker DJ. Levels of circulating semaglutide determine reductions in HbA1c and body weight in people with type 2 diabetes. Cell Rep Med. Sep 21 2021;2(9):100387. doi:10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100387

- Collins L, Costello RA. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists. [Updated 2023 Jan 13]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551568