This case study presents a 60-year-old woman came to the clinic with a history of moderate, generalized  plaque psoriasis covering 10% of her body surface area (BSA). Previous treatments included narrow-band UVB phototherapy (NBUVB). At her request, the physicians prescribed low-dose naltrexone (LDN) for a six-month period. The following is a summary of her treatment and discussion notes from the physicians using low-dose naltrexone for the treatment of psoriasis.

plaque psoriasis covering 10% of her body surface area (BSA). Previous treatments included narrow-band UVB phototherapy (NBUVB). At her request, the physicians prescribed low-dose naltrexone (LDN) for a six-month period. The following is a summary of her treatment and discussion notes from the physicians using low-dose naltrexone for the treatment of psoriasis.

The patient had a medical history mild osteoarthritis, however with no history of active joint pains or swelling. She was not on any medications and had no known drug allergies. A physical examination showed “well-demarcated, scaly, erythematous plaques covering 10% of her BSA.” She reported symptoms of pruritus but no pain.

Naltrexone, a μ-opioid receptor antagonist, is commonly used for opioid overdose with minimal side effects and no risk of physical dependence. Though LDN has not been formally studied in the treatment of psoriasis; is is known to possess anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory properties. This occurs because of its blockade of macrophage-released tumor necrosis factor (TNF).

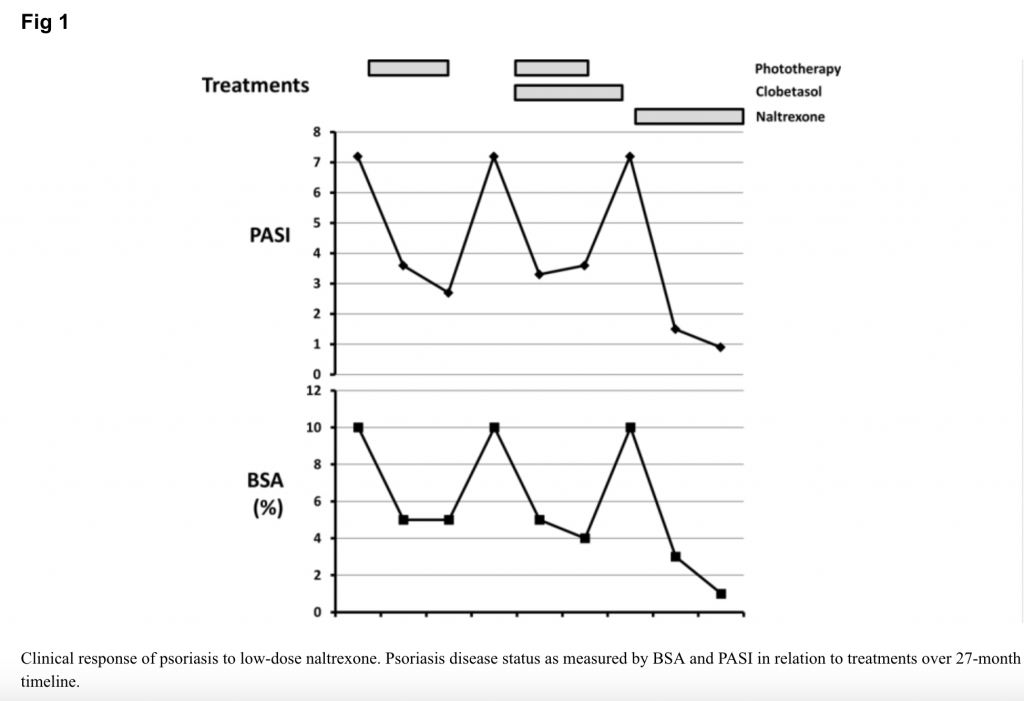

The patient began low-dose naltrexone, 4.5 mg daily, compounded by a specialty pharmacy. After 3 months of treatment, the patient’s psoriatic lesions were significantly improved at 3 months (see Figure 1). After 6 months, physicians recorded the following improvements:

- The affected BSA had decreased from 10% to 1% after treatment.

- The calculated PASI (psoriasis area severity index) score decreased from 7.2 to 0.9 after treatment.

- Symptoms of pruritus also improved with naltrexone.

- The patient did not take other adjuvant medications during this period. She did not report any side effects.

Low-dose naltrexone (less than 5 mg/d, or approximately one-tenth the dose used for substance use disorders) is believed to antagonize both μ-opioid receptors and nonopioid Toll-like receptors that are found on macrophages. This in turn, produces both pain-relieving and anti-inflammatory properties in a rather contradictory manner: 1. by increasing endogenous opioid release (in turn increasing ß-endorphin levels) and, 2. by mitigating the pro-inflammatory cascade promoted by macrophage-induced TNF activation.

Two recent case studies support this notion. Low dose naltrexone was recently shown to be an effective treatment for lichen planopilaris (a painful scalp condition that causes hair loss) and for Hailey-Hailey disease, a rare inherited dermatosis.

Given that traditional psoriasis treatments may not always be successful, affordable, or tolerable, this study shows that clinically LDN may have implications for patients who cannot tolerate other therapies or for whom other treatments have not been successful. The study authors note, “Although it is typically not possible to establish cause and effect with a single case, this is an interesting and novel finding that warrants further study. Treatment of psoriasis with low-dose naltrexone may be appealing because of its low side-effect profile, low cost, and its efficacy in patients with chronic inflammatory conditions.”