As you sit down to a dinner with family and friends you can learn a lot about the unique aspects of your tablemates’ metabolic response. Uncle Joe’s blood sugar may rise more from mashed potatoes than from Aunt Sue’s apple pie. But for your own blood sugar, the results could be quite the opposite. Research at the Weizmann Institute study published in the journal Cell, shows that people respond very differently to the same foods. The study authors believe that the reason’s vary from medical history and lifestyle to the state of one’s microbiome.

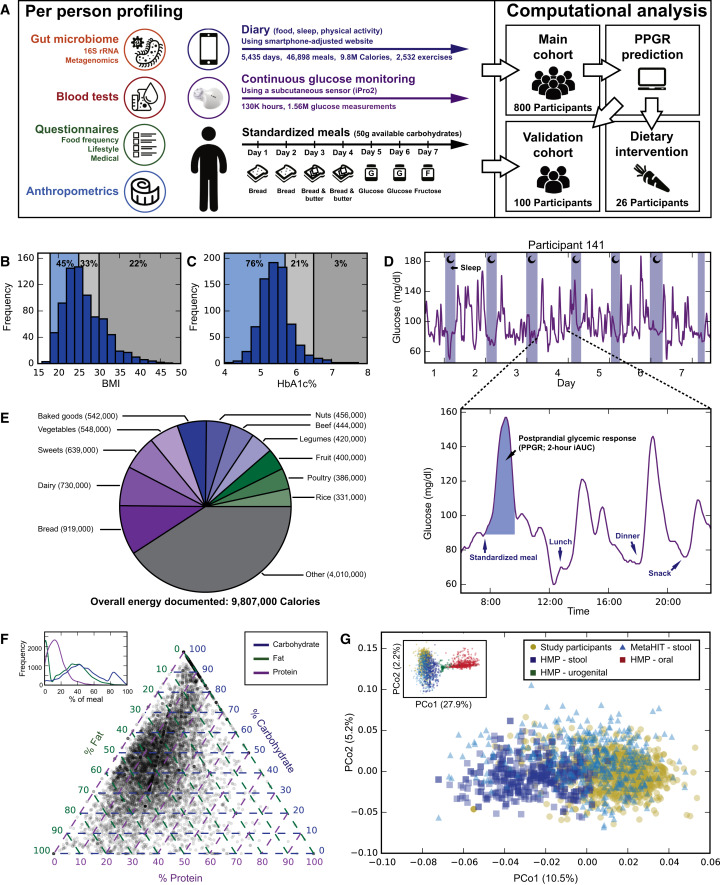

The Weizmann Institute “dinner table,” which included more than 800 cohorts of healthy and prediabetic individuals, was part of the Personalized Nutrition Project. Blood sugar was monitored continuously for one week, while they consumed a standardized glucose meal. The study also measured anthropometrics, physical activity, and self-reported lifestyle behaviors, as well as gut microbiota composition and function. See FIGURE 2.

FIGURE 2

The study was conducted by the groups of Prof. Eran Segal of the Computer Science and Applied Mathematics Department and Dr. Eran Elinav of the Immunology Department. Segal said: “We chose to focus on blood sugar because elevated levels are a major risk factor for diabetes, obesity and metabolic syndrome. The huge differences that we found in the rise of blood sugar levels among different people who consumed identical meals highlights why personalized eating choices are more likely to help people stay healthy than universal dietary advice.”

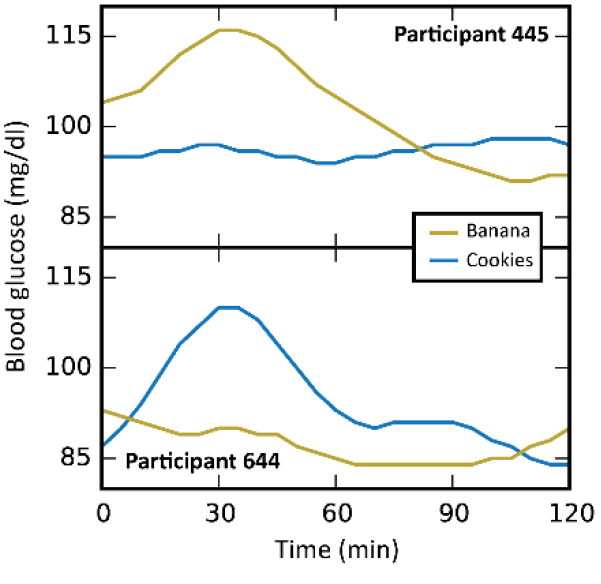

Segal and Elinav found remarkably different blood sugar responses to exactly the same foods. For instance, among 445 participants, blood sugar levels rose sharply after eating bananas but not after cookies, both with identical calories (SEE FIGURE 1). The opposite occurred in the other 644 participants. “Our aim in this study was to find factors that underlie personalized blood glucose responses to food. We used that information to develop personal dietary recommendations that can help prevent and treat obesity and diabetes, which are among the most severe epidemics in human history,” said Elinav.

FIGURE 1

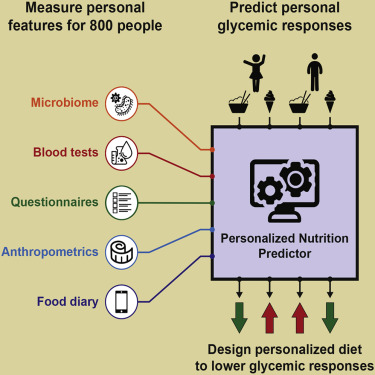

Scientists generated an algorithm for predicting individualized response to food based on the person’s lifestyle, medical background, and the composition and function of his or her microbiome. See below.

FIGURE 3

In a follow-up study of another 100 volunteers, the algorithm successfully predicted the rise in blood sugar in response to different foods, demonstrating that it could be applied to new participants.

In a follow-up study of another 100 volunteers, the algorithm successfully predicted the rise in blood sugar in response to different foods, demonstrating that it could be applied to new participants.

Here is a summary of what they found:

- Lifestyle also mattered. The same food affected blood sugar levels differently in the same person, depending, for example, on whether its consumption had been preceded by exercise or sleep.

- In the final stage of the study, the researchers designed a dietary intervention based on their own personalize algorithm to prescribe to each participant. Because of this individualized approach, some foods on a person’s “good” diet, were in another person’s “bad” diet.

- Within one week of the intervention, each person’s “good” diet kept blood sugar levels at a steady and healthy range, which the “bad” diets induced glucose spikes

- The individual’s “good” diets also reflected consistent changes in gut microbe composition.

CONCLUSION

The researchers suggest that the microbiome may be influenced by the personalized diets while also playing a role in participants’ blood sugar responses. The scientists are currently enrolling Israeli volunteers for a longer-term follow-up dietary intervention study that will focus on people with consistently high blood sugar levels, who are at risk of developing diabetes, with the aim of preventing or delaying this disease. To learn more, please visit www.personalnutrition.org.

Click Here for Full Text Study