Evidence has been mounting in recent years that additives like bisphenol-A (BPA), which are designed to improve plastics, can have wide-ranging effects on human health. Indeed, the well-publicized endocrine-disrupting effects of BPA have led to everything from initiatives to remove it from the water supply to a rise in popularity of “BPA-free” plastic products. And the plastics industry itself has responded by attempting to find safer alternatives for making plastics stiffer or more flexible.

All that effort may be in vain, however, as new research from Rutgers University, published April 23 in Particle and Fibre Toxicology, shows that plastics themselves can produce the same endocrine-disrupting effects as more-scrutinized additives. The disruption of sex hormones delivered by the endocrine system could help explain health issues such as increasing obesity and declining fertility.

The Study

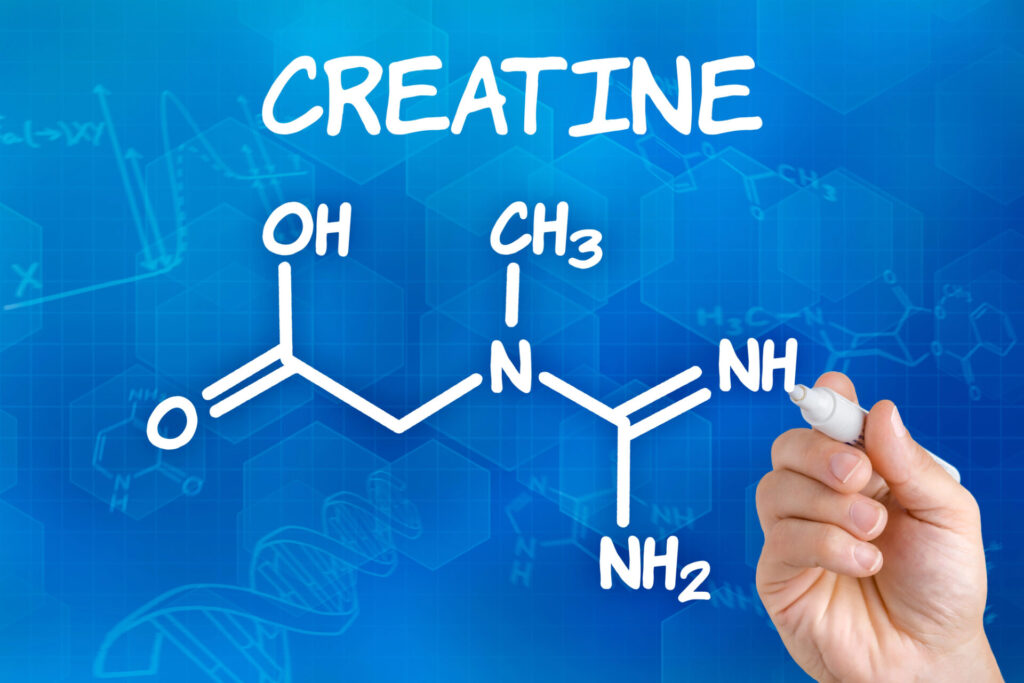

Researchers used an extremely fine, commercially available, food-grade nylon powder to test the effects of plastic inhalants on female rats in heat. They placed the powder onto a rubber pad and put the pad atop a bass speaker. The bass pulse sent the smallest nylon particles into the air, and air streams within the system delivered them to the rats.

The study aimed to assess the toxicological consequences of a single 24-hour exposure of microscale and nanoscale particles (MNPs) on the rats. After exposure, the researchers estimated the pulmonary deposits of MNPs and measured their impact on pulmonary inflammation, cardiovascular function, systemic inflammation, and endocrine disruption.

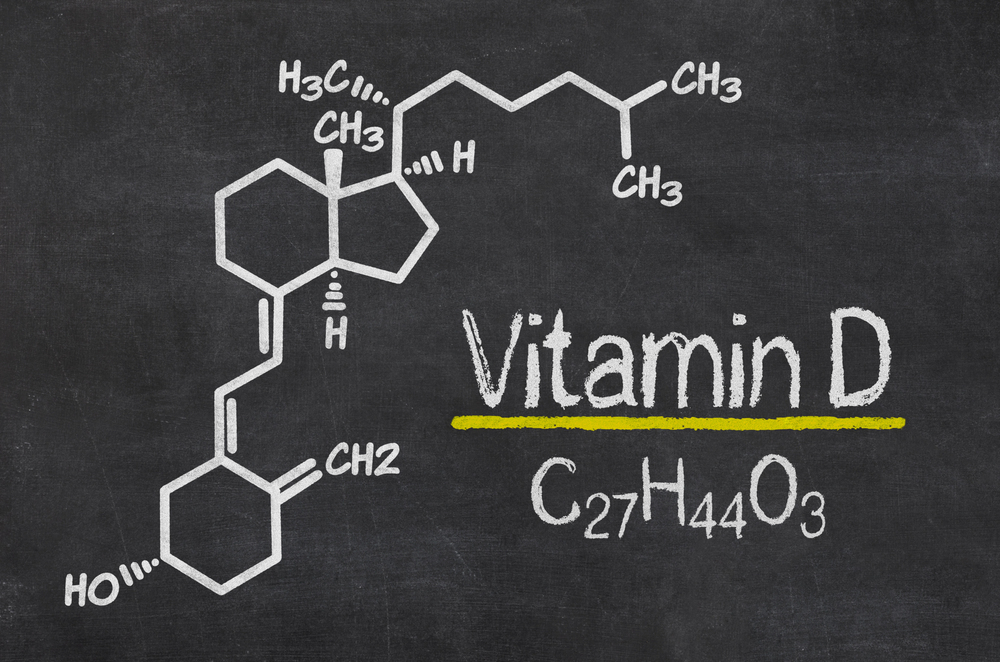

Pulmonary modeling suggested that inhaled particles were deposited in all regions of the rats’ lungs without causing significant pulmonary inflammation. However, the particles did produce endocrine-disrupting effects when inhaled by the rats in concentrations experienced by humans. Specifically, the researchers measured a decrease in the levels of the reproductive hormone 17 beta-estradiol in rats that were exposed to the plastic.

Conclusions

“Previous research has focused almost exclusively on chemical additives,” said Phoebe Stapleton, assistant professor at the Rutgers Ernest Mario School of Pharmacy and senior author of the study. “This is one of the first studies to show endocrine disrupting effects from a plastic particle itself…”

The study’s other breakthrough was in the method used to deliver the plastics to the rats. According to previous Rutgers research, about 80 percent of plastics are exposed to atmospheric forces that chip off invisibly small particles that float in the air we breathe. So the study more precisely mimicked human expose. “We figured out how to aerosolize the MNP to be inhaled just as we breathe it in real life,” Stapleton said.

Concern that these microplastics and nano-plastic particles could affect human health by disrupting our hormones is relatively new, Stapleton noted. Still, numerous studies have provided evidence that plastic chemical additives can have such an effect.

“Unfortunately, there’s very little that people can do to reduce exposure at the moment,” Stapleton said. “You can be aware of your flooring, wear natural fibers, and avoid storing food in plastic containers, but invisibly small plastic particles are likely in nearly every breath we take.”