Antibiotic resistance—when bacteria become impervious to the drugs intended to kill them—is an urgent global health crisis. In the U.S. alone, almost 3 million antibiotic-resistant infections occur each year, resulting in more than 35,000 deaths. As noted by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “If antibiotics…lose their effectiveness, then we lose the ability to treat infections and control these public health threats.”

And the threat may be even more dire than previously thought. According to a study published June 7 in Microbiome, the genes responsible for making bacteria resistant to antibiotics are even more prevalent in our environment than was suspected.

“We have identified new resistance genes in places where they have remained undetected until now,” says researcher Erik Kristiansson, a professor in the Department of Mathematical Sciences at Chalmers University of Technology and the University of Gothenburg in Sweden. “These genes can constitute an overlooked threat to human health.”

The Study

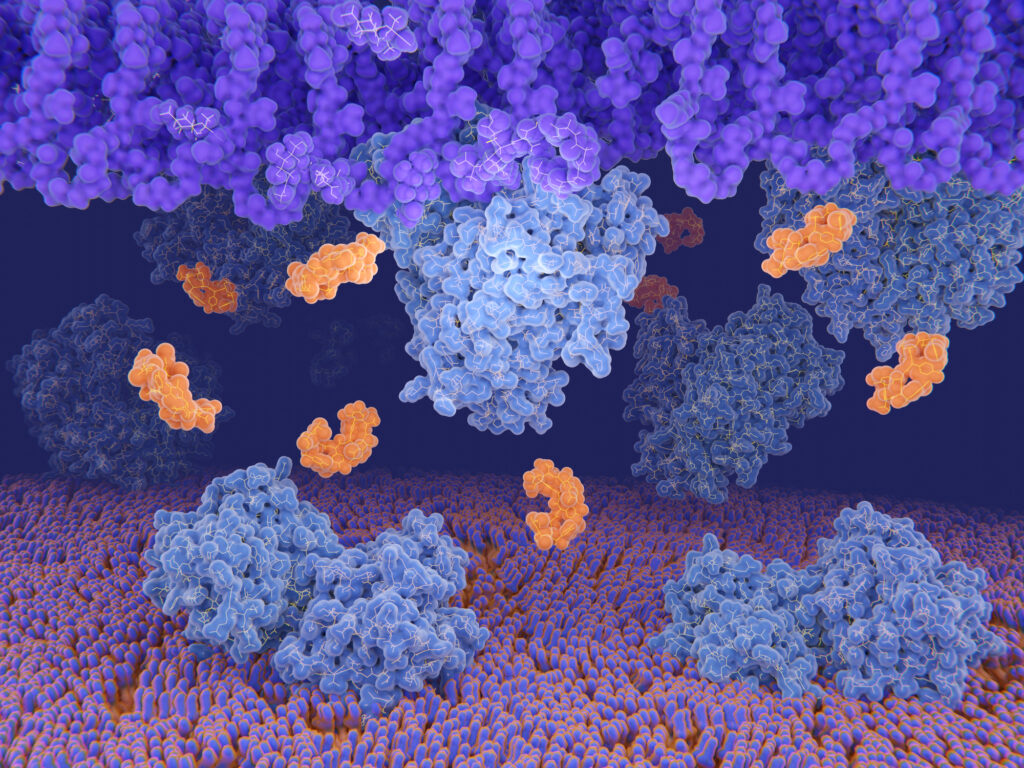

The genes that influence antibiotic resistance have long been studied, but the focus has generally been on identifying those that are already prevalent in pathogenic bacteria. Kristiansson and his team instead sifted through large quantities of bacterial DNA sequences to look for new forms of resistance genes in order to understand how common they are.

Using metagenomics, a methodology that allows the analysis of large quantities of data, they traced the genes in thousands of different bacterial samples from different environments, in and on people, in the soil, and from sewage treatment plants—a total of 630 billion DNA sequences in all.

Their results showed that the new antibiotic-resistance genes are present in bacteria in almost all environments, including the human microbiome—the symbiotic bacteria found in and on people. More alarmingly, the genes are found within pathogenic bacteria, which could lead to more difficult-to-treat antibiotic resistant infections.

The researchers discovered that resistance genes in bacteria that live on and in humans and in the environment were 10 times more abundant than those previously known. And of the resistance genes found in bacteria in the human microbiome, 75 percent were not previously known at all.

Conclusions

“Prior to this study, there was no knowledge whatsoever about the incidence of these new resistance genes. Antibiotic resistance is a complex problem, and our study shows that we need to enhance our understanding of the development of resistance in bacteria and of the resistance genes that could constitute a threat in the future,” says Kristiansson.

The research team is currently integrating their data into the international EMBARK project, which aims to take samples from sources such as wastewater, soil, and animals to chart how antibiotic resistance is spreading between humans and the environment.

“It is essential for new forms of resistance genes to be taken into account in risk assessments relating to antibiotic resistance,” says Johan Bengtsson-Palme, the EMBARK project’s coordinator. “Using the techniques we have developed enables us to monitor these new resistance genes in the environment, in the hope that we can detect them in pathogenic bacteria before they are able to cause outbreaks in a healthcare setting.”