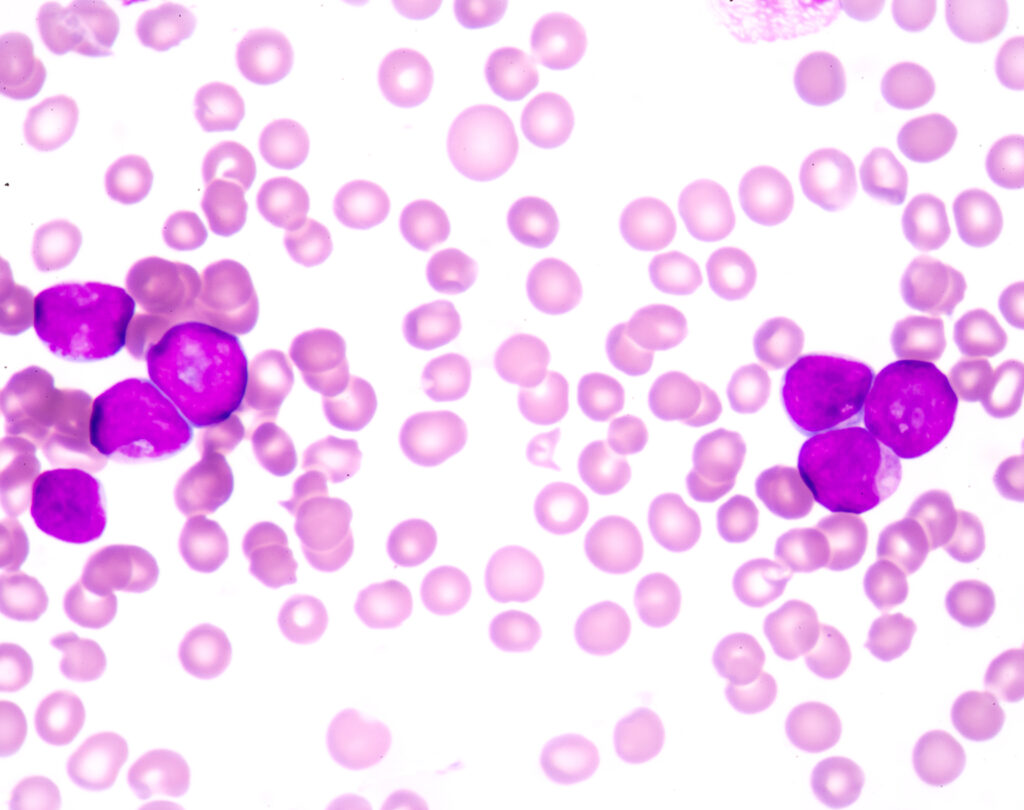

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML), the most common form of blood and bone marrow cancer among adults, is known for its rapid progression and resistance to treatment. “Treating acute myeloid leukemia is challenging because of these persistent, leukemia-initiating stem cells, which are typically not targeted by most existing therapies,” says Sandeep Prabhu, PhD, of Penn State University, the lead author of a new study published in the journal Cell Reports. “As a result, relapse of the disease is a big concern.”

Penn State scientists previously found that supplementing the diets of mice with selenium — a trace mineral found in many foods and dietary supplements — stimulated the production of compounds known as cyclopentenone prostaglandins (CyPGs), which appeared to kill or suppress leukemia stem cells.

“We had shown previously that if we supplement mice with selenium or we give them the CyPGs, we can treat their leukemia — make it less aggressive or even basically cure it,” says Robert Paulson, PhD, another of the new study’s authors. “We wanted to understand the mechanism of how that worked.”

The Study

The researchers hypothesized that a gene known as GPR44, which is activated by CyPGs, might play a role in the selenium-induced death of leukemia stem cells. GPR44 encodes a receptor that transmits signals from extracellular substances. When expressed on leukemia stem cells, it signals them to undergo programmed death.

To test their hypothesis, Prabhu’s team transplanted leukemia stem cells from mice without GPR44 to mice that had the GPR44 receptor. Groups of these mice were fed diets supplemented with varying amounts of selenium prior to the transplants. The team then observed disease progression among the various groups.

They found that mice with the GPR44 receptor that received selenium supplementation had significantly better outcomes than mice without the receptor. “In mice that lack the receptor, the leukemia becomes extremely aggressive — it’s like taking the brakes away,” says Prabhu.

Conclusions

Prabhu points out that while the selenium treatment induced leukemia stem cell death, it had no impact on normal blood-forming stem cells in the bone marrow, potentially making it a safe regimen that also could help ensure the recovery of normal blood cell formation during leukemia.

The fact that the researchers identified a receptor that initiates leukemia stem cell death is also a promising development for future treatments. “We think we have a good target now for developing therapies,” says Paulson. “When you test a new therapy, some patients would never respond to your drug because they just don’t have the right receptors. And now that we know that this receptor is key, we can tailor our tests with patient samples and target ones that we think will respond. That way, it’s more likely that we’ll identify a subset of leukemias that would be responsive to this kind of therapy.”

The researchers are now working with colleagues from Penn State’s College of Medicine to validate their findings, with the hope of proceeding to clinical trials with leukemia patients.