Women have historically used cannabis for menstrual pain, labor pain, hyperemesis gravidarum, appetite, urinary problems, uterine prolapse, postpartum hemorrhage, mastitis, migraine, nervous excitability and menopausal symptoms. While there is a lack of formal, contemporary research into effects of cannabis on women’s health (both pre-clinically and clinically) women have been the keepers of knowledge as they have wielded the healing properties of botanical medicine across cultures since prior to the time of written records.1

Felter’s “King’s American Dispensatory” in 1898 listed indications for cannabis: “Its effects upon the system vary under different conditions, thus: It lessens pain, checks spasmodic action, improves the appetite, causes sleep, exhilaration of spirits, and, in increased doses, inebriation, with phantasms, catalepsy, illusory delirium, and strong aphrodisia.” These early doctors could discriminate biphasic effects of cannabis: useful medicine at low dose, with increased side effects at high dose. These biphasic effects have been described in preclinical research but less so in formal human studies of cannabis effects, notably effects on pain, anxiety and sleep.2

It has been reported that from 2020-2021, cannabis sales to female customers increased by 55% and use is increasing over time, including during pregnancy, where there is no known safe level of cannabis use.3,4 Women experience more pain, depression and anxiety than men and more often have their symptoms dismissed or offered suppressive medications – left to negotiate root causes of health issues on their own. This is where naturopathic doctors often have a prime role, in providing evidence-based approaches.

What is the significance of cannabis use in women and for women’s health? The neurobiological basis of gender-biased effects of cannabis is a hormonal association with cannabinoid receptor expression. CB1 receptor is the most highly expressed receptor of its’ type (G protein-coupled receptor- GPCR) across the brain and is one of the main targets (along with the CB2 receptor) of the primary active ingredient in cannabis, Delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). THC has a much higher affinity for these receptors than our endogenous endocannabinoid compounds 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2AG) and N-arachidonoylethanolamine (AEA or anandamide). A secondary plant cannabinoid, cannabidiol (CBD) does not directly activate cannabinoid receptors and acts as a negative allosteric modulator, with weak affinity, when binding these receptors. CBD has been proposed to ‘indirectly’ active the endogenous cannabinoid system (endocannabinoid system: ECS) while CBD has actually been described as a ‘negative’ modulator of the ECS.5

Pain

From Felter: “As a remedy for pain, it ranks among the first; the more spasmodic the pain the better it acts. The neuralgic pains of depression are those most quickly relieved. It should be administered in painful states of the stomach, as gastric neuralgia, nervous gastralgia, in gastric ulcers, where opium is inadmissible, and in pain due to indigestion”. Chronic pain conditions exist with higher prevalence in women compared to men, including fibromyalgia, migraine, rheumatoid arthritis and reproductive-associated pain along with unmet needs for clinical approaches to pain. The costs of inadequate pain therapy in the U.S have been estimated at $635 billion annually, while loss of quality of life is priceless. There is a demonstrated role of the ECS in the regulation of pain transmission, and a preponderance of preclinical research showing that exogenous cannabinoids can modulate both the perception of pain and pain pathology in our body. Cannabis can be an important and effective herbal ally for chronic pain, providing a harm-reduction approach, by helping spare opioids or substitute for non-opioid pain relievers. THC is the primary constituent for analgesic potential of cannabis, however dose matters. Contemporary research has found that pain benefit can be lost with high potency cannabis.6

Anxiety

It is stated in King’s Dispensatory that the keynote for cannabis is “marked nervous depression”.

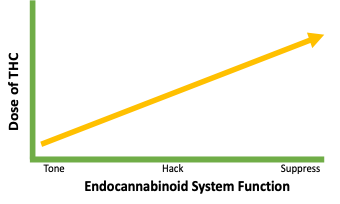

The ECS plays a homeostatic role in HPA axis function. A lot of people who use cannabis for medical benefit report that anxiety is the #2 reason they use cannabis (pain is #1).7 In fact, people who use cannabis for anxiety also report that they may decrease the use of anti-anxiety prescription medications.8 THC can be a good ‘hack’ for anxiety, but is not a fix for the underlying cause. Getting too high a dose of THC causes anxiety, increases social anxiety, can induce paranoia and more rarely psychosis.9 With the super potent THC products on the market today, it is being normalized to use this high potency cannabis. In fact, these super-potency products are almost purified drugs not resembling the whole plant. Anxiolysis is another cannabis application for women where informed dosing is required for THC effects on anxiety.

Depression

Felter again: “Cannabis is one of the most important of our remedies, but, like our best agents, it must not be used indiscriminately, but its cases should be specifically selected.” Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) can include irritability, depression, anxiety or a combination of the three. Does cannabis treat depression in women? The #3 reason that people who use medical cannabis is for depression, an area understudied in cannabis research for another condition primarily affecting women.10 While cannabis may lift mood or relieve anxiety in the short term, this is likely a hack and not treating the underlying cause. (see figure) In fact, overuse of cannabis by women (super-potency or frequency) may be contributing to depression. Early age onset of cannabis use by women may be a predisposing factor for depression.11 Felter had it right in stating that patients need to be carefully evaluated for medical cannabis, as there are genetic, environmental, social and hormonal contributions that should be considered. This highlights the need for healthcare providers being better informed about potential detrimental dose-related effects of THC and how to wisely wield this botanical medicine.

As a construct, it is likely that cannabis in a low-potency THC formulation (as cannabis originally grew) is an herbal ally for human health, beneficially modulating endocannabinoid function, while escalating doses can potentially lead to harm by suppression of the ECS and other neurotransmitter systems. Based on patient evaluation, a starting dose to tone the ECS could be 0.25-1 mg. of THC. Watch for forthcoming articles to help further your understanding of cannabis therapeutic dosing paradigms and the most appropriate roles for cannabis in women’s health across the lifespan!

Bio: Michelle Sexton, ND

Dr. Sexton is a trusted pioneer of clinical cannabis use teaching the ECS and cannabinoid medicine to healthcare providers since 2010.

After serving women as a midwife and herbalist since 1993, and gaining her ND degree from Bastyr University Seattle, Dr. Sexton completed a 3-year postdoctoral fellowship in the pharmacology of cannabinoids, studying the immunomodulatory effects of cannabinoids at the University of Washington.

She participated in the development of American Herbal Pharmacopoeia’s Cannabis monograph, which lacks the therapeutic compendium portion. Her educational role continues at the University of California San Diego, where Michelle is the only clinical ND in the University of California System and lead clinician at one of the first ‘cannabis clinics’ at at academic center in the US!

The Endocannabinoid System for Whole Person Assessment: A Clinical Companion This is an evidence-based companion guide to Dr. Sexton’s new book: “Eat, Sleep, Relax, Protect, Forget: An Endocannabinoid (ECS) Guide to Systems Wholeness for women. This guide is fully-referenced, and may contradict ‘herban legends’ of cannabis curative properties reflected in some of the marketing of cannabis, hemp and minor cannabinoids- many claims of which are not yet supported by the state of the science.Eat, Sleep, Relax, Protect, Forget: An Endocannabinoid (ECS) Guide to Systems Wholeness for Women

Eat, Sleep, Relax, Protect, Forget: An Endocannabinoid (ECS) Guide to Systems Wholeness for Women

Link to purchase my book at a discount:

Link to schedule a clinical consult for integrative practitioners:

References

- Wynn, R., Saints and sinners: women and the practice of medicine throughout the ages. JAMA, 2000. 283(5): p. 668-9.

- Shustorovich, A.C., J; Wallace, MS; Sexton, M, Biphasic Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoid Therapy on Pain Severity, Anxiety and Sleep Disturbance: A Scoping Review. Pain Medicine, 2024.

- Metz, T.S., EH, Is Increasing Frequency of Marijuana Use Among Women of Reproductive Age a Cause for Alarm? JAMA Network Open, 2019. 2(7).

- Practice, C.o.O., Committee opinion NO. 722: marijuana use during pregnancy and lactation. Obstet Gynecol, 2017. 130(4): p. e205-e209.

- McPartland, J.M., et al., Are cannabidiol and Delta(9) -tetrahydrocannabivarin negative modulators of the endocannabinoid system? A systematic review. Br J Pharmacol, 2015. 172(3): p. 737-53.

- Wallace, M.S., et al., Efficacy of Inhaled Cannabis on Painful Diabetic Neuropathy. J Pain, 2015. 16(7): p. 616-27.

- Sexton, M., et al., A Cross-Sectional Survey of Medical Cannabis Users: Patterns of Use and Perceived Efficacy. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res, 2016. 1(1): p. 131-138.

- Corroon, J.M., Jr., L.K. Mischley, and M. Sexton, Cannabis as a substitute for prescription drugs – a cross-sectional study. J Pain Res, 2017. 10: p. 989-998.

- Viveros, M.P., E.M. Marco, and S.E. File, Endocannabinoid system and stress and anxiety responses. Pharmacol Biochem Behav, 2005. 81(2): p. 331-42.

- Sexton, M., Cuttler, C, Finnell JS, Mischley, LK, A Cross-Sectional Survey of Medical Cannabis Users: Patterns of Use and Perceived Efficacy. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research, 2016. 1(1): p. 131-138.

- Rabiee, R., et al., Cannabis use and the risk of anxiety and depression in women: A comparison of three Swedish cohorts. Drug Alcohol Depend, 2020. 216: p. 108332.