Primary care is shifting from solely the doctor’s office to culinary nutrition kitchens. Why? Health and wellness and even disease therapies are much more than prescription medicine. Among medical professionals who get this, hundreds of hospitals and clinics across the country have been adding teaching kitchens to their square footage. And, best news yet, when health care administrators and patient care providers team up with culinary and nutrition experts, patients achieve long-term health and wellness by learning the art of cooking.

At the Truman Medical Center in Kansas City, a pilot program called crEATe began in 2015 as a way to teach healthcare providers culinary nutrition skills in a state of the art demonstration kitchen. The hospital’s Executive Chef Andre Yusus teached culinary skills in partnership with Jeneta Culton, RD, LDN, the clinical nutrition manager. “We decided to start the pilot with doctors and providers since they would be able to impact a higher number of patients at the start,” Culton said when the program launched. Now two years in the program, TMC offers classes one day a week to patients.

If you’ve ever considered a similar program and were stymied by fear that it wouldn’t work, Harvard School of Public Health published a feasibility study in May 2017 for a prototype teaching kitchen scenario. The study was significant in that it was more than just cooking, nutrition lessons. The program was highly personalized with the aid of wellness coaches who explored the principles of mindful eating and journaling to help participants understand barriers and success patterns.

David Eisenberg, MD, lead researcher of the study from Harvard who has championed the idea of medical teaching kitchens from concept to reality, believes the future of medicine has to start at a stove rather than an exam table. “There are now hundreds of teaching kitchens. And I think the idea has found receptivity across the country,” said Eisenberg in a recent PBS News Hours interview (see the PBS video here). “We have now got Cleveland Clinic. We have got Kaiser Permanente. We have got Harvard, and Princeton, and the University of Texas, and 20 other university systems making this available to their patients or their trainees.”

Here is how the participants progressed through the program.

Research staff worked with subject matter experts in the fields of nutrition, culinary arts, exercise, health coaching, and mindfulness to develop a TK self-care curriculum that combines didactic instruction with experiential learning in each of the above-mentioned areas. The program included one 2.5-hour evening meeting per week and one 5-hour Saturday meeting every other weekend over the course of the 16 weeks (80 hours for the first cohort; scaled back to 70 hours over 14 weeks for the second cohort due to scheduling constraints of the Culinary Institute of America (CIA), Hyde Park, New York.

During the weekday classes, which were facilitated by a research member (either an MD, RD, or MPH), participants watched a chef educator demonstrate cooking techniques necessary to prepare simple, healthy meals at home (eg, whole grain cookery, stock and soup basics, salad composition, and salad dressing techniques). Participants then listened to a lecture by a subject matter expert and/or participated in discussions about one of the other educational topics, including nutrition, movement, and mindfulness.

There were no dietary prescriptions, and the intake during the study was ad libitum. However, the educational components, for example, didactic instruction with regard to why certain foods should be encouraged and others discouraged and the scientific rationale for these recommendations, were conveyed in the hope of altering subjects’ dietary choices and behaviors over time. With complementary access to a local gym facility and a personal activity-tracking device provided by the study, individuals were encouraged to increase their physical activity throughout the program. Participants were also matched with a paid certified health coach (through Wellcoaches®) who provided regular 30-minute phone calls up to once a week throughout the duration of the 14- to 16-week program in order to help participants leverage their personal motivation to change relevant behaviors. The research team created a general overview of the curriculum but made minor changes to the weekly classes based on weekly feedback from participants.

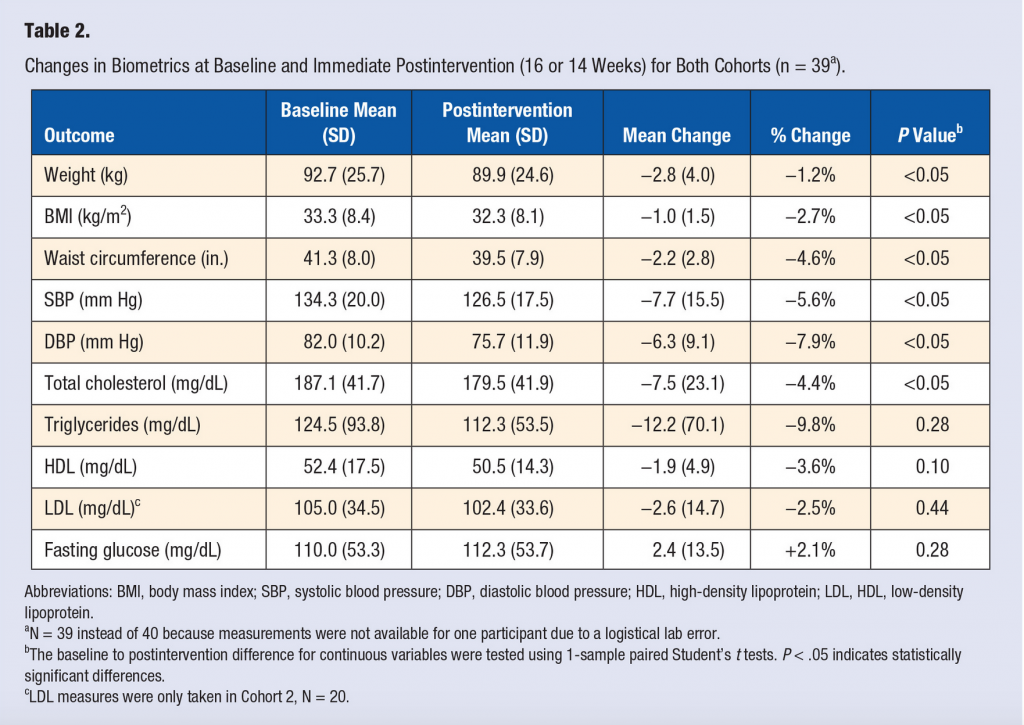

The fact that the program was relatively non-prescriptive in regard to diet might lead you to think the failure rate would be high. Not so. Here is what the results showed (see Table 2 for more below).

- Feasibility was assessed for ease of recruitment and attendance among 40 participants.

- All 40 participants completed the program with high attendance (89%) and response rates on repeated assessments.

- Multiple changes were observed in biomarkers and self-reported behaviors from baseline to post program including significant ( P < .05) decreases from baseline to post program in body weight (−2.8 kg), waist circumference (−2.2 in.), systolic and diastolic blood pressure (−7.7 and −6.3 mm Hg, respectively), and total cholesterol (−7.5 mg/dL).

- Participants showed improvements from baseline to end of program in the following measures: cooking meals from scratch at home more often, cooking convenience and ready-made meals less often, reading nutrition labels on purchased foods more often, and feeling more confident cooking, following a recipe, tasting new foods, and cooking new foods and recipes. All of these improvements persisted but appeared to have diminished slightly at 6 and 12 months (researchers cite a lack of built-in follow up for the pilot program) .

If this might be a good option for your practice, then check out the Healthy Kitchen Healthy Lives conference at the Culinary Institute of America in St Helena, Calif. The conference is an opportunity to sharpen your culinary nutrition skills with 500 fellow colleagues and the world’s leading culinary and nutrition experts who designed this feasibility study. “At this conference, we bring in some of the top nutrition scientists in the world to say, look, here’s the evidence that eating these foods either keeps you healthy or reduces your risk of disease, whereas eating these foods really speeds up your risk of disease, heart disease, cancer, diabetes,” says Eisenberg.

Download the Harvard Study Here