Many of you may be reading the term “Culinary Genomics” for the first time. You might be wondering who coined the term, what does it mean and how does it relate to genomic medicine. Let’s first deconstruct term, then we will give you a working definition and a specific example how it can be used with patients or clients to translate principles and concepts of genomic medicine into savory, nutrient-rich culinary dishes. By Amanda Archibald, RD, founder of Genomic Kitchen

What is Culinary Genomics?

Two years ago, I introduced the term at the Annual Meeting of the Institute for Functional Medicine in Austin, Texas in a presentation, Translational Nutrigenomics. The intent was to let healthcare professionals from around the world know that that we had devised a methodology to blend genomic medicine with the culinary arts. The genomic medicine revolution had been underway since the early 2000s with the completion of the Human Genome Project and the introduction of clinical genomic testing by some forward-thinking laboratories. At the same time, the culinary arts were achieving acclaim and great success with the many food shows on cable channels as well as mainstream media. The Food As Medicine movement with its focus on food as a foundation to healing was also gaining traction among the public and healthcare providers. However, the link between genomic medicine, nutrition and the kitchen itself had not been made. So, I worked with experts in Genomic medicine and nutrition science, and with her background in the culinary arts, culinary genomics was born.

Inner Workings of Culinary Genomics

Before we examine the application of culinary genomics to clinical practice, let’s look at a working definition of Culinary Genomics:

The integration of foods and bioactives with demonstrated nutrigenomic activity onto a whole foods, nutrient rich canvas, to optimize a person’s health and well-being.

Let’s dissect this a little. Culinary genomics requires a deep understanding of, and appreciation for the current research in three scientific areas: cell biology, biochemistry and the culinary arts. A clinician must know about transcription and translation and how these processes are used to replicate DNA and how bioactives (phytochemicals) in the foods we eat can initiate a conversation with the nucleus of a cell via cell signaling pathways.

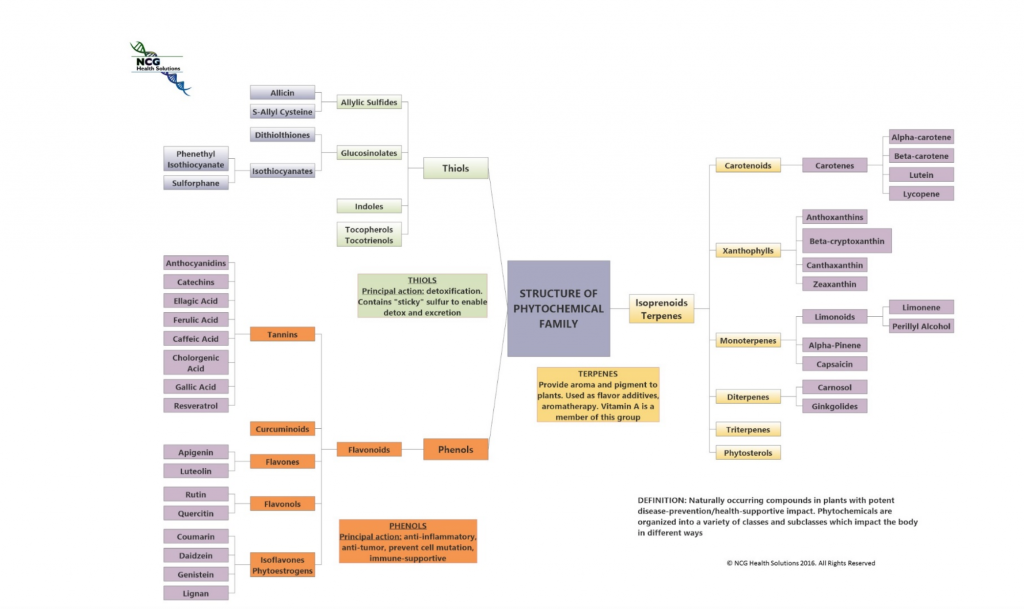

Bioactives are non-nutritive components found in food (mostly plants) that have demonstrated health-conducive properties. Examples of bioactives include flavonoids, carotenoids and glucosinolates (see attachment). Bioactives are capable of registering a stress signal to the cell, not strong enough to alter redox balance, but strong enough to initiate a biochemical cascade culminating in gene expression (or not). Culinary genomics considers which bioactives have demonstrated nutrigenomic activity or nutrient-gene crosstalk in human cells and adds them to a culinary toolbox. But this is only one third of the equation. See Figure 1.

FIGURE 1

Biochemistry and Culinary Genomics

The second component of culinary genomics is an understanding of biochemistry. Bioactives play a crucial role in gene expression resulting in protein transcription (production). But proteins such as enzymes which participate in chemical reactions in the body, sometimes require nutrient cofactors to facilitate their work. Culinary genomics (or culinary translation of genomic information) forces clinicians to think in terms of biochemical pathways that are associated with our patient’s health goals. For example, if the goal is to reduce oxidative stress, culinary genomics might consider up-regulating the Nrf2 gene. Nrf2 transcribes for 5 potent intracellular redox enzymes which require nutrient cofactors (selenium, magnesium, iron, etc) to thwart an reactive oxygen species challenge. Therefore, by combining knowledge of bioactives and nutrient cofactors to support biochemical processes clinicians can achieve the desired health outcomes.

The Kitchen and Culinary Genomics

The third and last component of Culinary genomics is the kitchen. The kitchen requires skills in technique but  more importantly creativity. Technique refers to how we work with ingredients containing delicate bioactives. Bioactives are both heat and acid sensitive, requiring us to think about ways to preserve the integrity of the bioactives in recipe preparation and menu development, in order to harness the power of their food-gene conversations. Next is creativity. Preserving bioactives requires developing menus that combine both cooked and raw approaches AND working with a targeted toolbox of ingredients rich in bioactives and cofactors. Remember: this new culinary field hinges upon the use of bioactives with demonstrated nutrigenomic activity. We are, therefore, working with very specific ingredients and their flavor profiles. As the field of nutrigenomics evolves, more ingredients will be added to the toolbox, but for now, we are working with evidence-based specifics.

more importantly creativity. Technique refers to how we work with ingredients containing delicate bioactives. Bioactives are both heat and acid sensitive, requiring us to think about ways to preserve the integrity of the bioactives in recipe preparation and menu development, in order to harness the power of their food-gene conversations. Next is creativity. Preserving bioactives requires developing menus that combine both cooked and raw approaches AND working with a targeted toolbox of ingredients rich in bioactives and cofactors. Remember: this new culinary field hinges upon the use of bioactives with demonstrated nutrigenomic activity. We are, therefore, working with very specific ingredients and their flavor profiles. As the field of nutrigenomics evolves, more ingredients will be added to the toolbox, but for now, we are working with evidence-based specifics.

Applying Culinary Genomics to Clinical Practice

Let me say this straight up: you do not have to be a chef to apply culinary solutions to patients in a clinical practice. I work with professional chefs in this new field and as you might imagine they are super excited about the healing potential associated with these ingredients. To reiterate, culinary genomics is a precise discipline requiring an understanding of genomics, nutrition science (biochemistry) and how to apply these principles to personalized health solutions.

The first step to utilize culinary genomics with patients in a clinical practice it to prioritize health goals to the ingredients that supply information, or biochemistry to the cells. In other words, you map out your care plan with the ingredients that will help you achieve a patient’s health outcomes. More importantly, this process helps you explain to a patient the underlying reasons you are recommending specific ingredients. Once a patient understands the inner workings of food, enthusiasm sets in.

[quote]Handing out recipes carte blanche without the deeper context of how an ingredient works is just handing out another tasty recipe. Food matters. Words matter.[/quote]

Culinary Genomics in Action

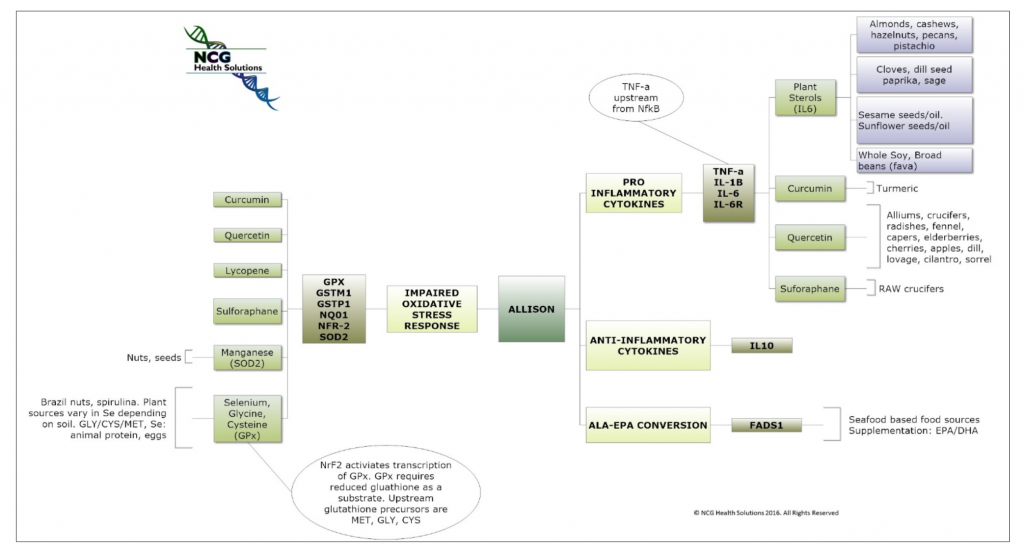

The second graphic, FIGURE 2, represents a culinary translation of genomic information I presented in 2016 along with Dr. Bobbi Kline, co-founder of Genoma International, at a scientific conference for healthcare professionals. Essentially, this roadmap prioritizes the health interventions for our example patient, Allison, based on genomic test results.

FIGURE 2

The blocks that are shaded in yellow are her health priorities. Adjacent to each health priority are the gene SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms) or variants from her genomic test results (blocks shaded in green), prioritizing her health intervention goals. In the outer area of the graphic, the bioactives AND the nutrient cofactors are listed for each health condition, which will support her nutrigenomic intervention. In short, the graphic reflects a culinary genomic map, outlining a route from genomic test results to the kitchen, to the table, to the meal, providing the specific bioactives and ingredients to “speak” to Allison’s biochemistry. Culinary genomics embraces both the cutting edge of science and the newest discipline in the kitchen. Culinary genomics offers tremendous potential and rewards for both clinician and patient.

LEARN MORE ABOUT AMANDA’S GENOMIC KITCHEN