Going to the doctor’s office is a stress-inducing event for many people But for Blacks, it can be particularly terrifying, because of something called negative racial stereotyping. And while racial stereotyping may not be intentional, it can seep into a patient’s psyche in ways you might not realize. A first-of-its-kind study by researchers at USC and Loyola Marymount University (LMU) has found evidence that the persistent health disparities across race may, in part, be related to anxiety about being confronted by negative racial stereotypes while receiving healthcare.

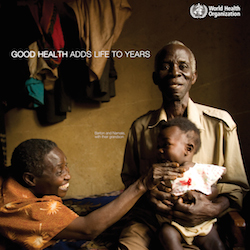

The researchers, USC’s Cleopatra Abdou and LMU’s Adam Fingerhut, found that Black women who strongly identified with their race were more likely to feel anxious in a healthcare setting – particularly if that setting included messaging that promoted negative racial stereotypes, even if inadvertently. Posters can be one source of this negative stereotyping. In light of this research, Today’s Practitioner tracked down some positive messaging for Blacks that you can download for your office (high-resolution downloads available below).

The researchers, USC’s Cleopatra Abdou and LMU’s Adam Fingerhut, found that Black women who strongly identified with their race were more likely to feel anxious in a healthcare setting – particularly if that setting included messaging that promoted negative racial stereotypes, even if inadvertently. Posters can be one source of this negative stereotyping. In light of this research, Today’s Practitioner tracked down some positive messaging for Blacks that you can download for your office (high-resolution downloads available below).

“This may help to explain some of the as yet unaccounted for ethnic and socioeconomic differences in morbidity and mortality across the lifespan,” said Abdou, assistant professor in the USC Davis School of Gerontology and the Department of Psychology in the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. “Historically, the discourse surrounding health and health disparities has focused on nature, nurture, and the interaction of the two. With this study, we are bringing situation and identity into the equation.” By Cleopatra M Abdou and Adam W Fingerhut, published in the American Psychological Association journal Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, July 21, 2014, Vol. 20.

Stereotype threat, which is the threat of being judged by or confirming a negative stereotype about a group you belong to, has already been shown to influence the outcome of standardized testing, such as performance on the SAT (the most widely used college admissions exam). For example, when confronted with a negative stereotype about their group identity, some Black students become anxious that they will perform poorly on a test and, thereby, confirm negative stereotypes about the intellectually ability of people of their race. As a consequence of cognitive load from this performance anxiety, students actually become more likely to perform poorly.

It is already well documented that Black women underutilize healthcare when compared to white women – possibly hurting their health overall. Abdou and Fingerhut’s research suggests that this underutilization could be prompted by anxiety and other socioemotional consequences of stereotype threat.

Participants in Abdou and Fingerhut’s study sat in virtual doctor’s waiting and exam rooms, which displayed posters depicting Black women confronting unplanned pregnancy or AIDS — conspicuous examples of negative health-relevant racial stereotypes.

Black women who reported that they felt a strong connection with their ethnicity or ethnic group experienced the highest levels of anxiety while waiting in the rooms with the posters, while white women with a strong connection to their ethnicity experienced the lowest anxiety levels, suggesting that strong white identity may provide immunity from healthcare-related stereotype threat, Abdou said. Women of either group with low ethnic identity fell in the middle of the range.

“This is stereotype threat-induced anxiety,” Abdou said. “It’s important to note that this anxiety is not present when we don’t prime highly identified African American women with negative stereotypes of African American women’s health.”

This research represents the first-ever empirical test of stereotype threat in the health sciences. Although stereotype threat theory is popular in the social sciences, with hundreds of studies documenting its effects on academic and other types of performance in recent decades, Abdou and Fingerhut are the first to experimentally apply stereotype threat theory to the domain of healthcare and health disparities more broadly.

This research represents the first-ever empirical test of stereotype threat in the health sciences. Although stereotype threat theory is popular in the social sciences, with hundreds of studies documenting its effects on academic and other types of performance in recent decades, Abdou and Fingerhut are the first to experimentally apply stereotype threat theory to the domain of healthcare and health disparities more broadly.

“This study is important as a first step to understanding how stereotypes play out in healthcare settings and affect minority individual’s experiences with healthcare providers. Further research is needed to understand the potential downstream effects, including reduced trust in physicians and delay in seeking healthcare as a way to avoid stereotype threat, which may have long-term implications for health among Blacks,” said Fingerhut, associate professor at the LMU Bellarmine College of Liberal Arts.

Posters like the ones Abdou and Fingerhut used can be commonly found in doctors’ offices to promote admirable goals, such as AIDS awareness, but the use of specific ethnicities in their messaging can have unexpected negative consequences, Abdou said.

“There is value in public health messaging that captures the attention of specific groups, particularly the groups at greatest risk; but we have to be mindful of unintended byproducts of these efforts and think outside the box to circumvent them,” Abdou said.

The research was funded by the Michigan Center for Integrative Approaches to Health Disparities and the USC Advancing Scholarship in the Humanities and Social Sciences Initiative.