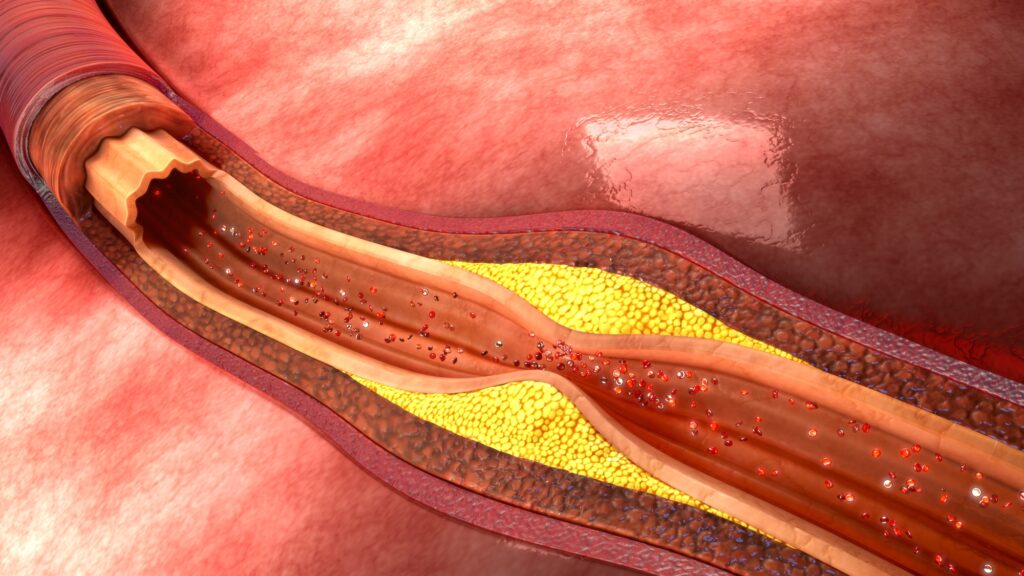

It is well-known that being physically unfit at a young age is linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease much later in life. But the mechanism behind this finding has never been fully understood. With that in mind, an international team led by researchers from Linköping University in Sweden set out to investigate whether physical fitness in youth is linked to atherosclerosis—the accumulation of plaque in the arteries, which is an important risk marker for cardiovascular disease—later in life. Their results were published in February in the British Journal of Sports Medicine.

To determine the link between early fitness and later atherosclerosis, the researchers linked information from the Swedish Military Conscription Register to the Swedish Cardiopulmonary Bioimage Study (SCAPIS), a large population study on heart and lung health in individuals aged 50 to 64 years. The search uncovered conscription data from the 1970s and ’80s on 8,986 men participating in the SCAPIS study, giving researchers an average follow-up time of 38 years.

The researchers mapped data on the men’s cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular strength, body mass index (BMI), and other factors from the conscription register to their current condition. They examined atherosclerosis in the large arteries from the heart up to the brain with ultrasound and also used coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) and coronary artery calcium (CAC) scores to examine plaques in the coronary arteries.

“We measured not only calcified plaques in the coronary arteries, but also non-calcified plaques, which are considered more problematic. They may be more likely to rupture, which can cause heart attacks, and have a worse prognosis,” says researcher Ángel Herraiz-Adillo, PhD.

Analysis showed that the highest physical fitness group (high cardiorespiratory fitness and muscular strength) had a 33% lower risk for severe coronary stenosis compared with those with the lowest physical fitness.

Conclusions

One significant drawback of the study, the researchers say, is its gender exclusivity. Since only men did military service in Sweden at the time, the researchers have only been able to investigate the long-term association between physical fitness and atherosclerosis in men. It is therefore not possible to draw conclusions for women from this particular study.

That said, the results both confirm previous research and offer new insights into the link between fitness in youth and health in middle age.

“We see in our study that both good cardiorespiratory fitness and good muscle strength in youth are associated with a lower risk of atherosclerosis in the coronary arteries almost 40 years later,” says Pontus Henriksson, PhD, senior associate professor at the Department of Health, Medicine and Caring Sciences at Linköping University. Furthermore, he says, the results suggest that coronary atherosclerosis is likely one of the mechanisms underlying the association between physical unfitness in youth and later cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality.

“Our results support the clinical value of assessing both cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness for cardiovascular risk stratification,” the researchers wrote. “Long-term interventions able to improve both cardiorespiratory fitness and muscular strength in adolescents could contribute to prevention of atherosclerosis in adulthood.”