In recent years, exposures to environmental toxic metals, including arsenic, lead, cadmium, mercury, and

Exposure to arsenic, lead, and cadmium showed a positive and approximately linear association with the risk of cardiovascular disease. Mercury was not associated with any cardiovascular outcomes.

While these elements occur naturally in the earth’s crust, certain metals can also appear at unsafe levels in drinking water, food, and air as a result of agricultural and industrial practices, mining, and smoking, the research team notes in The BMJ. Copper and lead, for example, can seep into drinking water from corroded pipes, while arsenic and cadmium can accumulate in groundwater due to runoff from factories and crop irrigation systems and are also found in cigarette smoke.

Toxic Metals and Cardiovascular Disease Study Analysis

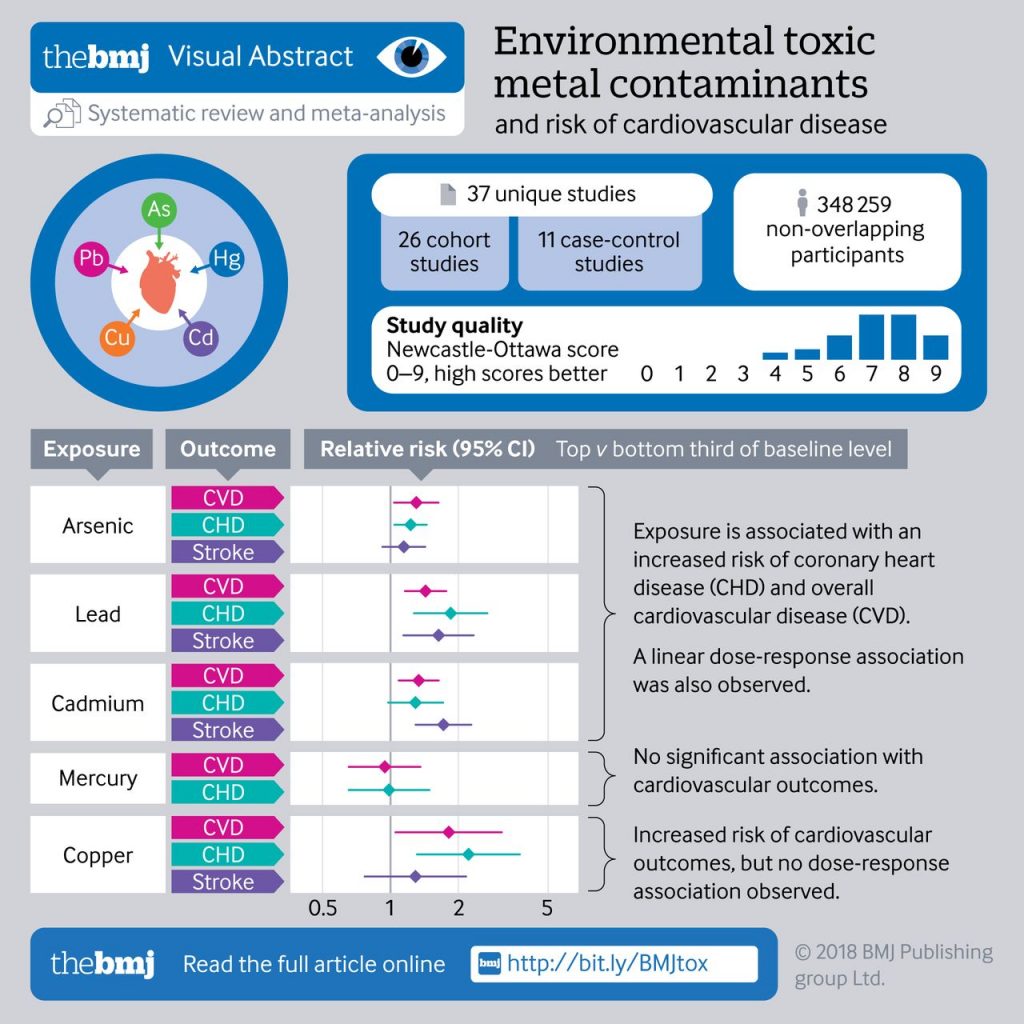

To help clarify the evidence, researchers summarized the available population based epidemiological studies in a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the associations of selected metal contaminants (measured at individual level) with the risk of first-ever cardiovascular outcomes (including cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, and stroke), and quantify any dose-response relation.

For the analysis, researchers examined data from 37 earlier studies with a total of almost 350,000 participants. Overall, about 13,000 people had heart attacks, bypass surgery or other events related to heart disease and about 4,200 had a stroke.

- Compared to people with the lowest levels of arsenic exposure, those with the highest exposure were 30 percent more likely to develop cardiovascular disease.

- The highest levels of lead exposure were tied to a 43 percent higher risk. Two key pathways by which lead has been implicated in the risk of cardiovascular disease are mediation through accelerated systolic blood pressure and damage to renal function.

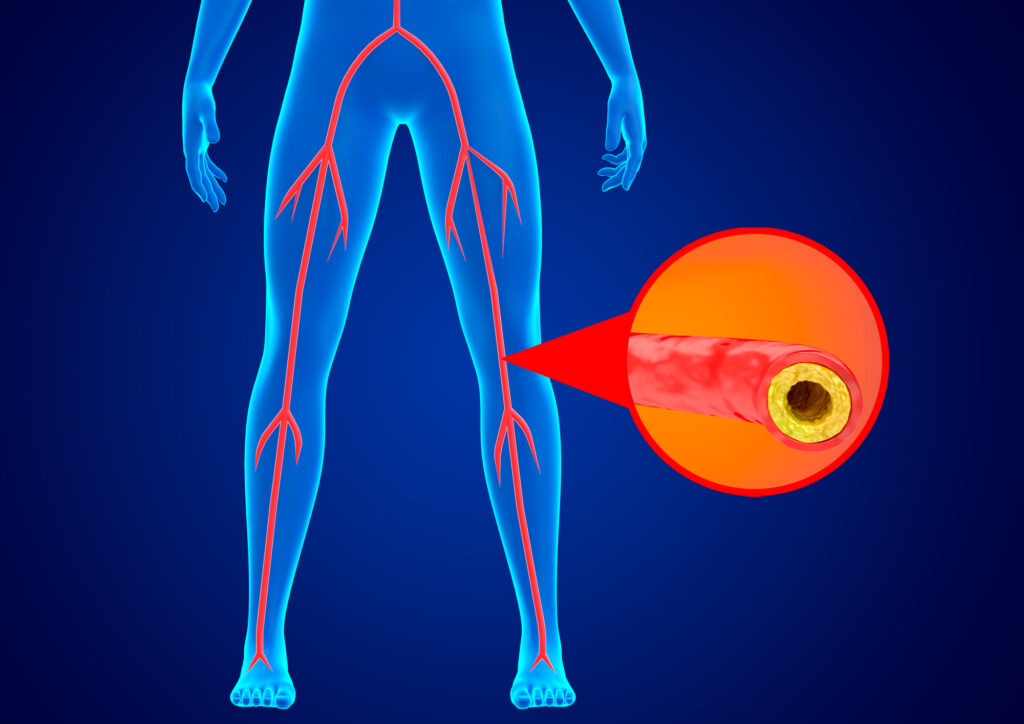

- Top levels of cadmium were linked to 33 percent higher risk. Cadmium’s adverse effects on the vascular system are thought to be mediated by oxidative stress, inflammation, and endothelial cell damage, which can result in atherosclerosis. This is important as cadmium is widely prevalent in groundwater and common plant-based foods (eg, rice and vegetables).

Study Characteristics

A total of 37 unique studies reporting on 348 259 distinct patients were identified, including relevant available data on arsenic (12 studies), lead (11), cadmium (8), mercury (9), and copper (6). Average baseline levels of contaminants in studies reporting baseline exposure ranged from:

- 3.7 μg/L to 4.9 μg/L for arsenic in urine,

- 0.7 μg/L to 131.1 μg/L for arsenic in drinking water,

- 2.6 μg/dL to 44.3 μg/dL for lead,

- 0.44 μg/L to 1.3 μg/L for cadmium,

- 0.004 μg/L to 3.5 μg/L for mercury,

- 0.96 mg/L to 1.27 mg/L for copper.

Association Between Environmental Contaminants Cardiovascular Disease, Coronary Heart Disease and Stroke Risk

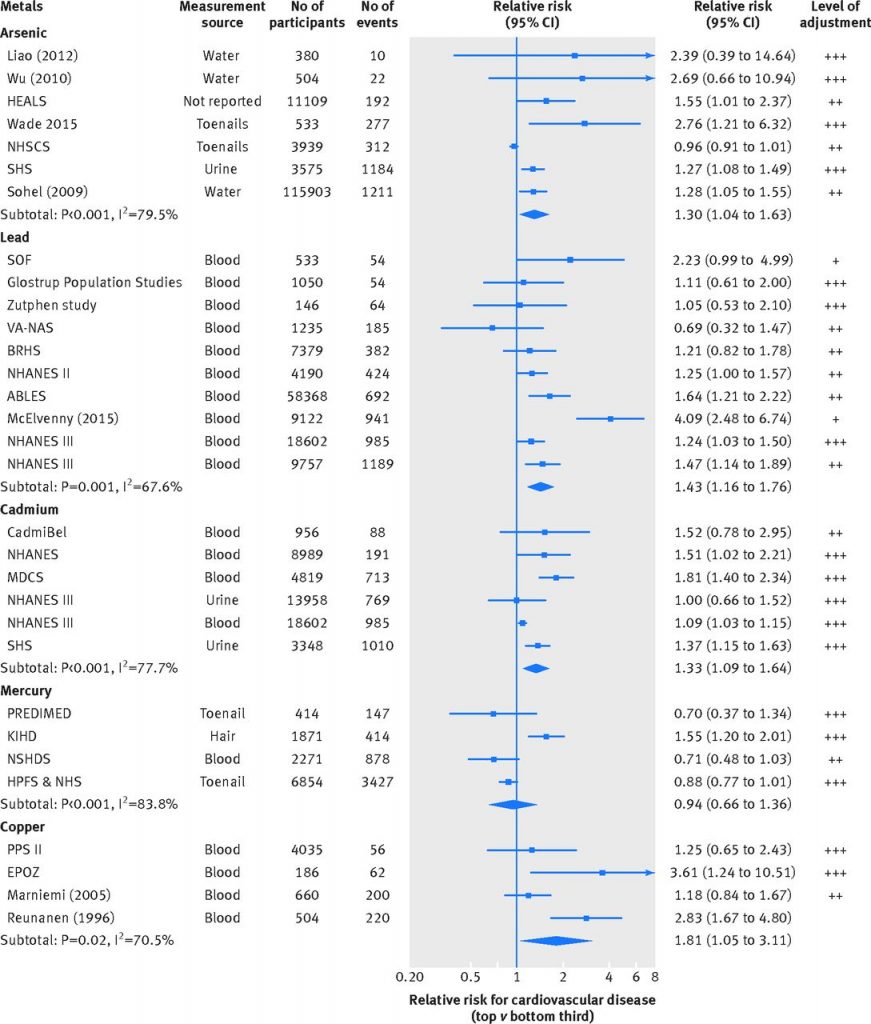

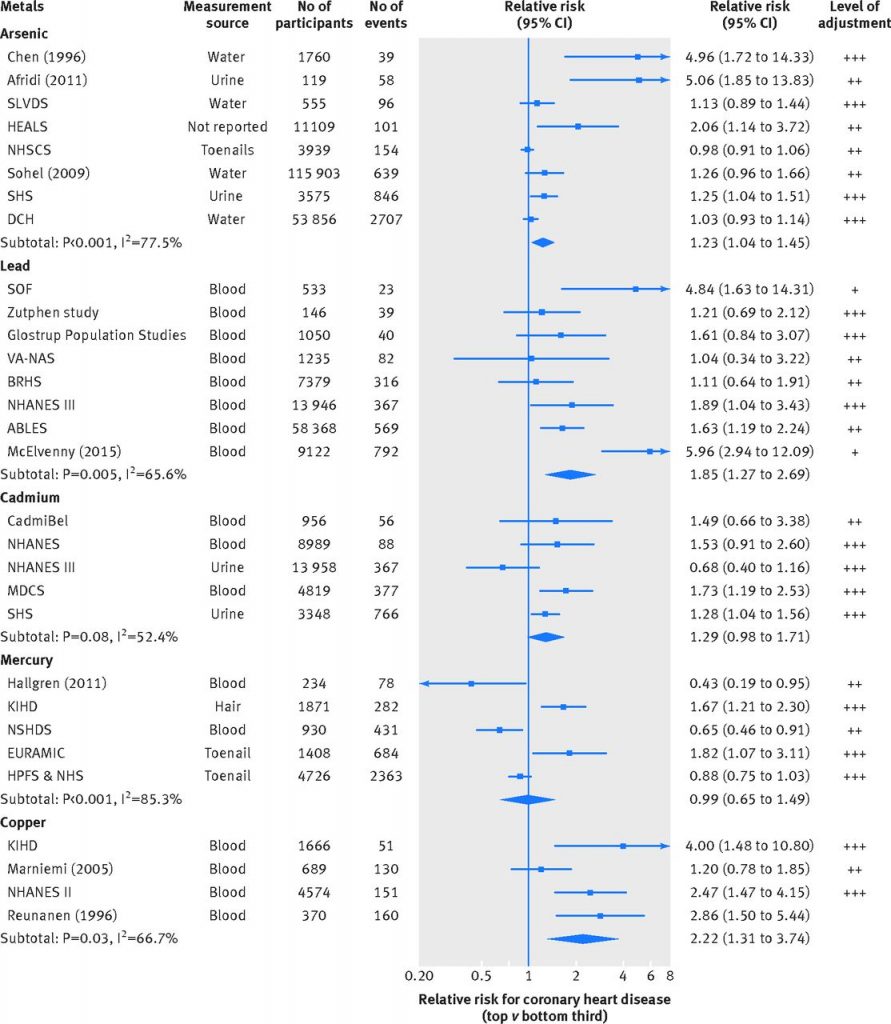

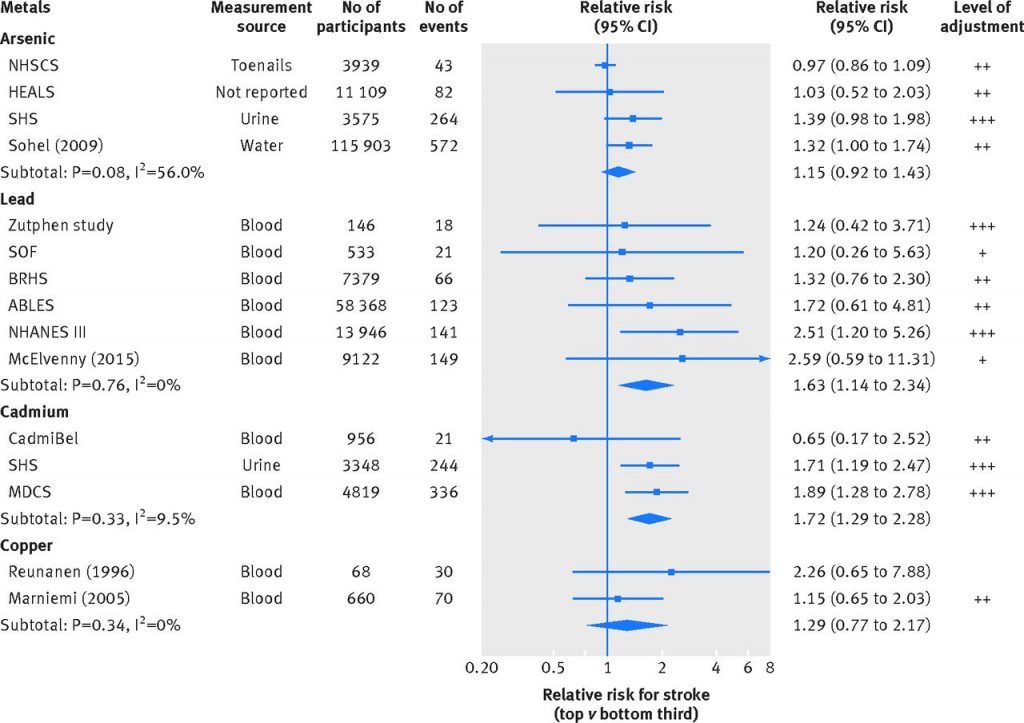

In total, 14,706, 12,033, and 3613 cases of cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, and stroke, respectively, across 35 contributing studies were included in the meta-analysis. The total follow-up duration ranged from five to 36 years in the prospective studies. Twenty three studies adjusted for conventional risk factors for cardiovascular disease including age, sex, and sociodemographic factors (ethnicity, education, income) as well as additional risk factors such as smoking status, blood pressure, lipids, and medical history. Thirteen studies adjusted for age, sex, and sociodemographic factors. Three studies adjusted for age and sex only. See FIGURE 3, 4 and 5 below.

FIGURE 3 Cardiovascular Disease Risk

Association between environmental contaminants and cardiovascular disease. NR=not reported; +=minimally adjusted (typically adjusted for age and sex only); ++=adjusted for at least one non blood based cardiovascular risk factor (eg, systolic blood pressure, body mass index, history of diabetes, etc); +++=additionally adjusted for at least one blood based cardiovascular risk factor (eg, total cholesterol, c-reactive protein, etc).

Association between environmental contaminants and coronary heart disease. NR=not reported; +=minimally adjusted (typically adjusted for age and sex only); ++=adjusted for at least one non blood based cardiovascular risk factor (eg, systolic blood pressure, body mass index, history of diabetes, etc); +++=additionally adjusted for at least one blood based cardiovascular risk factor (eg, total cholesterol, c-reactive protein, etc).

Figure 5 Stroke Risk

Association between environmental contaminants and stroke. NR=not reported; +=minimally adjusted (typically adjusted for age and sex only); ++=adjusted for at least one non blood based cardiovascular risk factor (eg, systolic blood pressure, body mass index, history of diabetes etc); +++=additionally adjusted for at least one blood based cardiovascular risk factor (eg, total cholesterol, c-reactive protein, etc.

Clinical Conclusion / The researchers note:

Our findings may have important policy and scientific implications. Firstly, these findings highlight the importance of environmental toxic metals in enhancing cardiovascular risk, beyond the roles of conventional behavioral risk factors (such as tobacco use and unhealthy diet).

Presently, in clinical practice, toxicity for these metals, if suspected, are established through a range of diagnostic investigations including blood and 24-hour urinary analyses and typically involving an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry analytical technique for elemental determinations. Treatment options for heavy metal toxicity include various antidotes and chelating agents (which enhance the elimination of metals from the body) such as succimer (DMSA), unithiol (DMPS), sodium calcium edetate, and dimercaprol. However, since efficacy and response of these therapies vary greatly, primary prevention, by developing evidence based public health guidelines and innovative low cost, scalable interventions to reduce human exposure to these contaminants, should be prioritized.

To gain access to this article and the rest of our extensive database of full-text articles, please register below or log in here.