When it comes to diet advice for heart health, we’ve all heard the same thing — reduce your sodium intake. Turns out, that may not be the best approach for everyone.

According to a study in Heart, a publication from the British Medical Journal, restricting salt intake may actually worsen a common form of heart disease for some people — particularly younger people and those of black and other ethnicities.

The optimal restriction range for salt in heart failure (from less than 1.5 g to less than 3 g daily) and its effect on patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction isn’t clear, as they have often been excluded from relevant studies.

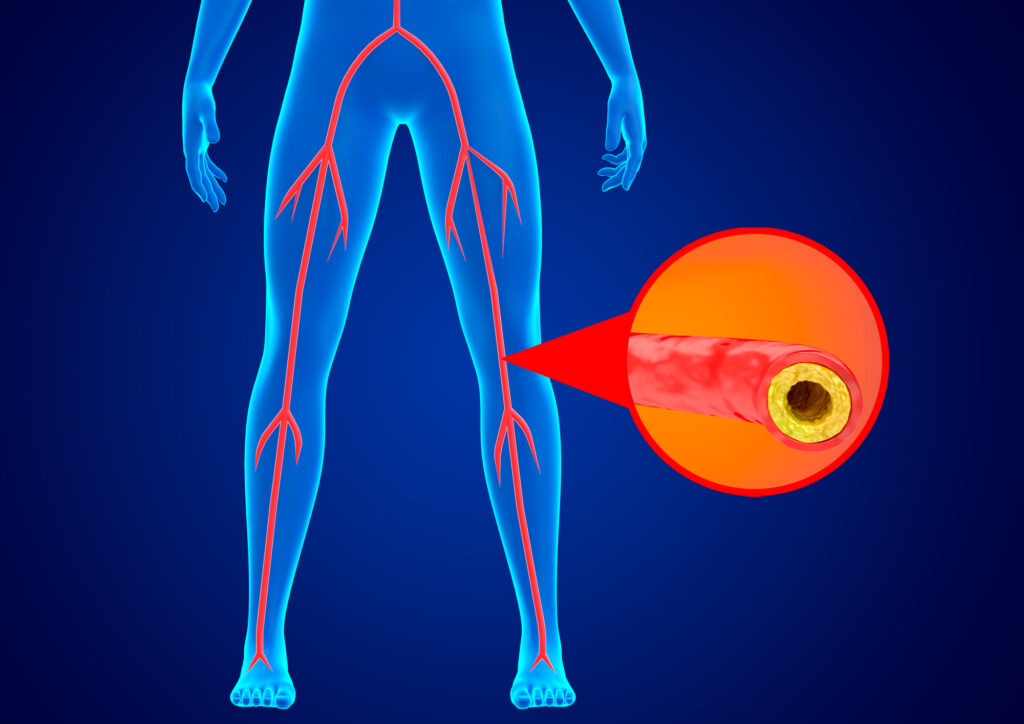

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, which accounts for half of all heart failure cases, occurs when the lower left chamber of the heart (left ventricle) isn’t able to fill properly with blood (diastolic phase), so reducing the amount of blood pumped out into the body.

To explore this salt intake association further, researchers drew on secondary analysis of data from 1,713 people aged 50 and above with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction who were part of the TOPCAT trial.

Study Details

A phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, this trial was designed to find out if the drug spironolactone could effectively treat symptomatic heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.

Participants were asked how much salt they routinely added to the cooking of staples, such as rice, pasta, and potatoes; soup; meat; and vegetables, and this was scored as: 0 points (none); 1 (⅛ tsp); 2 (¼ tsp); and 3 (½+tsp).

Their health was then monitored for an average of 3 years for the primary endpoint, a composite of death from cardiovascular disease or admission to hospital for heart failure plus aborted cardiac arrest. Secondary outcomes of interest were death from any cause and death from cardiovascular disease plus hospital admission for heart failure.

Subjects with Low Salt Scores:

Around half the participants (816) had a cooking salt score of zero: more than half of them were men (56%) and most were of white ethnicity (81%). They weighed significantly more and had a lower diastolic blood pressure (70 mm Hg) than those with a cooking salt score above zero (897).

They had also been admitted to hospital more often for heart failure, were more likely to have type 2 diabetes, poorer kidney function, to be taking meds to control their heart failure, and to have a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (lower cardiac output).

Subjects with High Salt Scores:

Participants with a cooking salt score above zero were at significantly lower risk of the primary endpoint than those whose score was zero, mainly driven by the fact that they were less likely to be admitted to hospital for heart failure. But they were no less likely to die from any cause or from cardiovascular disease than those whose cooking salt score was zero.

“Those aged 70 or younger were significantly more likely to benefit from adding salt to their cooking than were those older than 70 in terms of the primary endpoint and admission to hospital for heart failure.”

Similarly, those of black and other ethnicities seemed to benefit more from adding salt to their cooking compared with those of white ethnicity, although the numbers were small.

Gender, previous hospital admission for heart failure, and the use of heart failure meds weren’t associated with heightened risks of the measured outcomes and cooking salt score.

Conclusion

Overstrict cooking salt intake restriction was associated with worse prognosis in patients

with HFpEF, and the association seemed to be more predominant in younger and non-white patients. Clinicians should be prudent when giving salt restriction advice to patients with HFpEF.